Bound, gagged and told to shut up… Conversations with Polly Borland

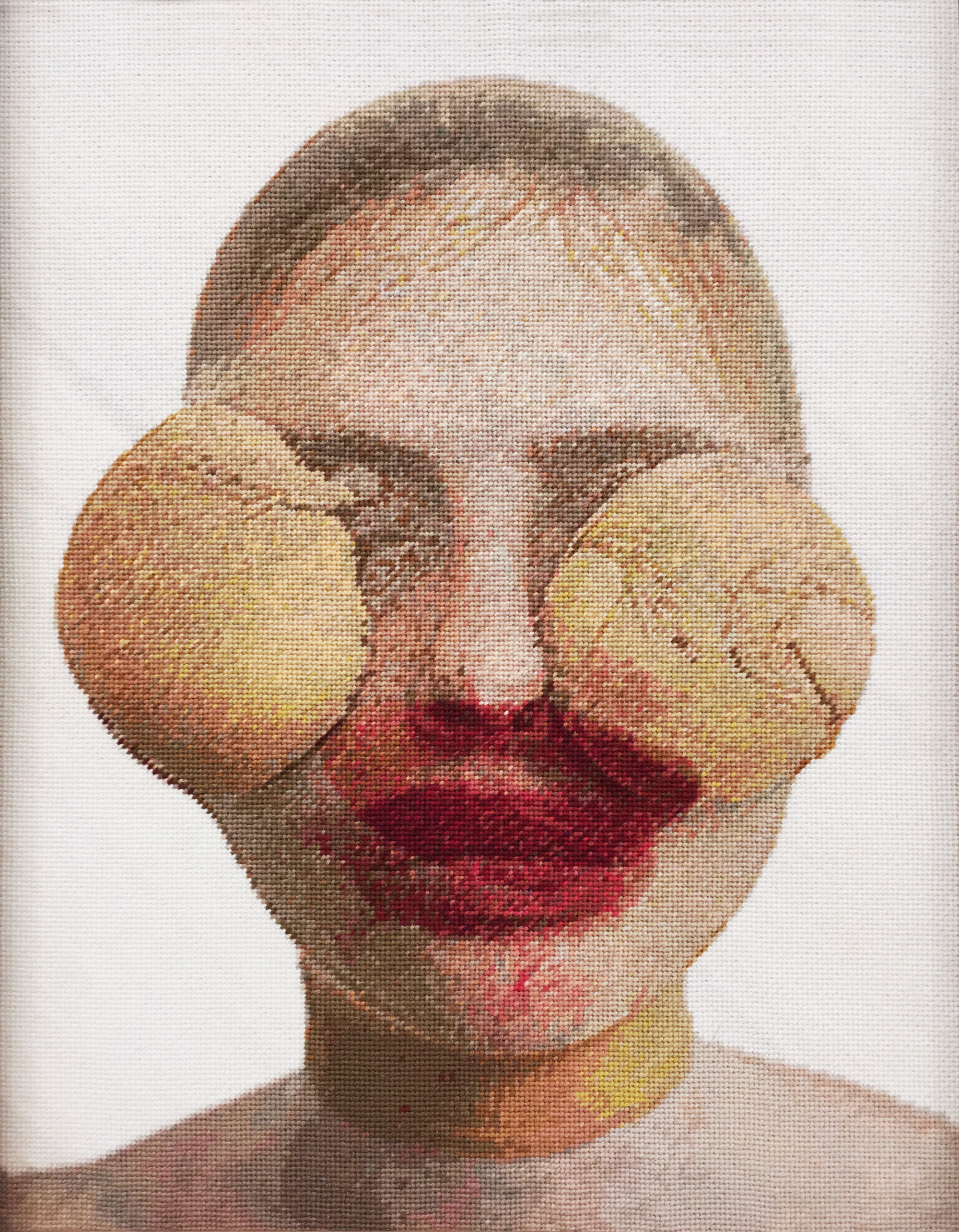

image above: Polly Borland, Mouth 2017, reversible tapestry, 64 x 53 cm

© Polly Borland, Courtesy the artist and Murray White Room, Melbourne

by Andy Rijs

Two weeks ago, after the opening of my own exhibition, I trudged through the pouring rain to find my way to the opening of Monster, an exhibition of photography and tapestry works by the renowned Melbourne born photographer Polly Borland, currently showing at Murray White Room. As thunder crashed down outside I walked through a room that was warm from body heat, filled with hordes of people buzzing with energy, and I found myself struck by the foreboding imagery on the walls before me.

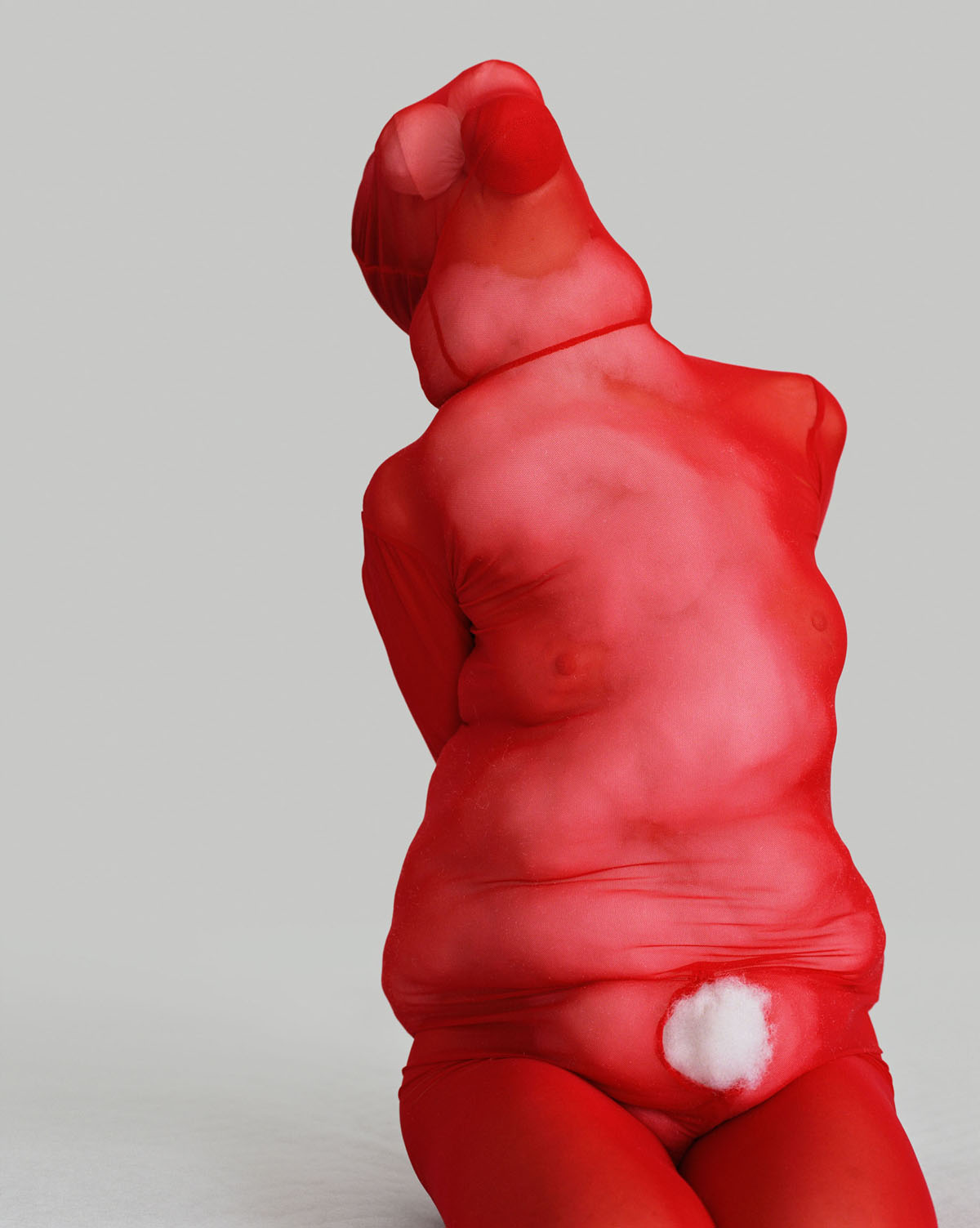

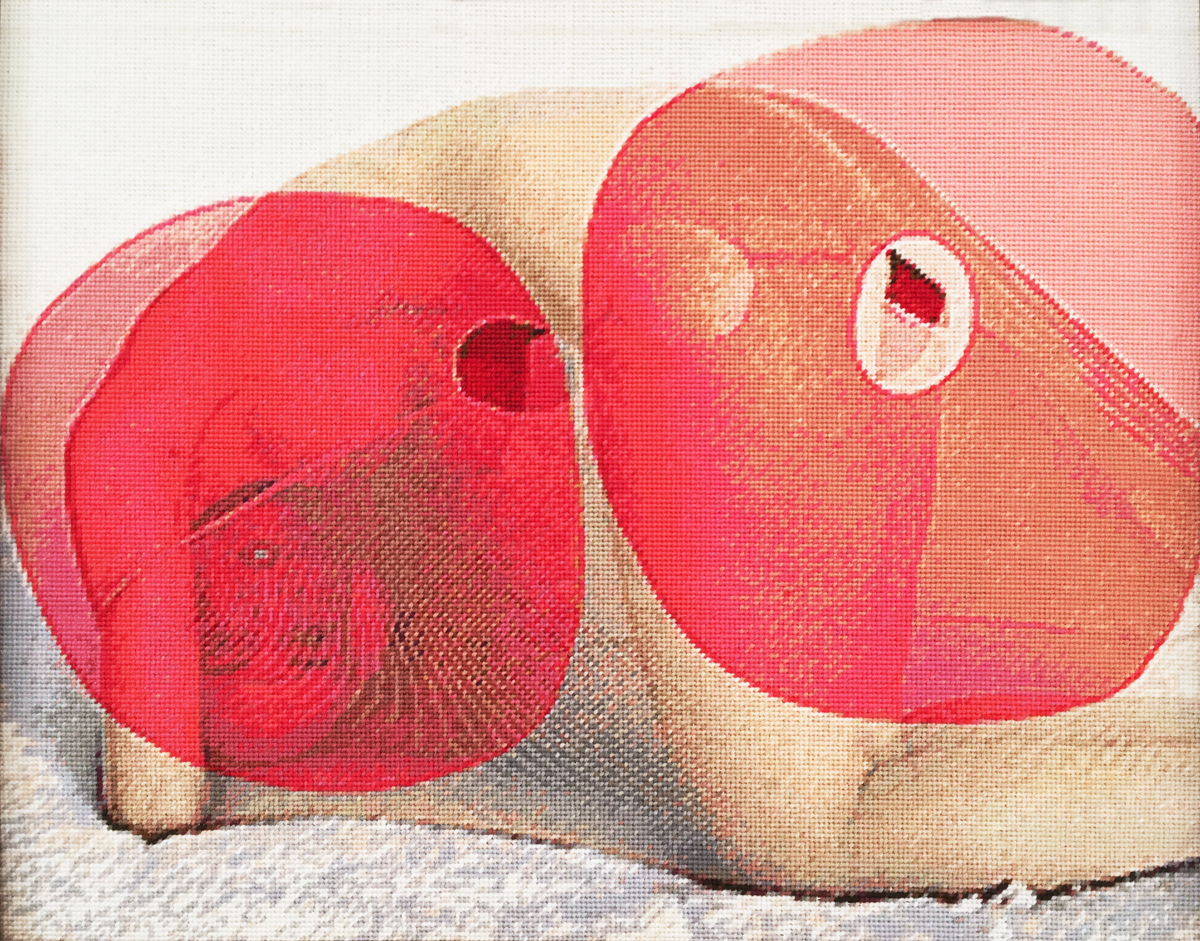

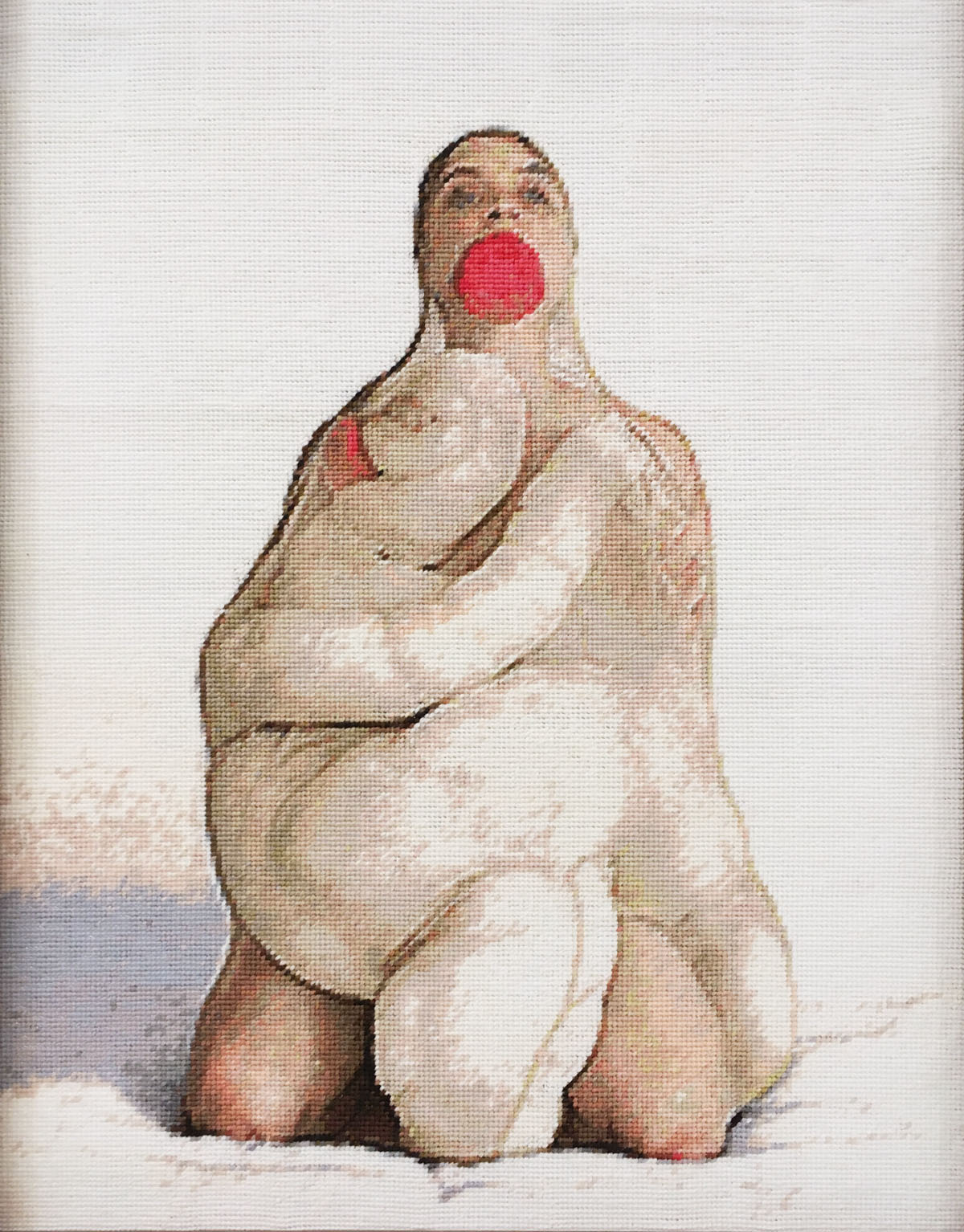

Fleshy figures, bound in body stockings, disfigured and debauched, with smears and blotches of red loomed forward from the pristine white walls. It could have been like walking into a scene where something dark and sinister had occurred, yet in Borland’s usual playful style these figures, though bound and gagged, had an unmistakable beauty and alluring presence to them. Their dark eroticism subdued by their materiality, captured like snapshots into tapestries that upon close inspection you could have mistakenly thought were scenes your grandmother had lovingly stitched.

This is a new feature in Borland’s work, who until recently had only shown photography. Walking around the exhibition another surprise element struck me as a gallery assistant came along and flipped one of the works around, revealing another work on the backside – excuse the pun. Curious to hear what was motivating Borland when she produced these works I approached her, nervously at first. There’s something about Polly Borland, with her bright red hair, large glasses and unapologetic self-assuredness that feels like she could easily be a Hollywood movie star. As it turns out she has actually been living in Los Angeles with her film director husband John Hillcoat and their sixteen year old son Louie for the past six years while she produced this body of work. I had the good fortune to be able to meet up with Borland twice after this initial awkward introduction, and we discussed life, her work, her career, her experience of living in Los Angeles and the culture shock that informed this work.

Fleshy figures, bound in body stockings, disfigured and debauched, with smears and blotches of red loomed forward from the pristine white walls.

Rijs: After you completed art school you predominantly worked as an editorial photographer for a long time. What brought about the shift when you began focusing on producing work as a visual artist?

Borland: While I was at Prahan College in the 80s, which is the Victorian College of the Arts now, every semester you had to produce a body of work, and it was totally self-generated. Back then if you were a photographer and you were good, you did all of it. You did editorial, you did portraiture, you did fashion, you did your own work… So I was doing all of it, but mainly focused on photographing people. It was actually one of the technicians at Prahan College that suggested I do fashion. In a way now when I look back on it, the directions that I went after I left college were not the direction I really should have taken. I was desperately trying to be a fashion photographer and it never really panned out, because although I like clothing, I don’t really think I’m a natural fashion photographer.

Eventually, around the early to mid 90s I realised that the editorial world was sucking me dry and I needed to really focus on my own personal work. So, I stopped doing fashion and I was doing a bit of reportage work – which is sort of like photojournalism – and I was beginning to be known for offbeat reportage and quirky subjects like the Star Trek people, to nudists, to you name it. Then a friend of mine told me about this phenomenon called adult babies. So I went and did a magazine article of them, but none of them would allow their faces to be seen. Six months later I went back to them and said ‘I want to do a book, but you are going to need to reveal your identity’. They were the ones that I really connected well with, and I had honoured my word and protected their anonymity, so they said ‘okay, fine’. So that started a five year project, and that’s really when I re-engaged with my own personal work properly.

Polly Borland, Daisy wrestling at lil’ kathi’s party 1994-99, archival pigment print, 67.6 x 101.6 cm

© Polly Borland, Courtesy of Murray White Room, Melbourne

Rijs: What was it about adult babies and that scene that really interested you?

Borland: I found it fascinating on lots of different levels – visually, and on an aesthetic level. I found it kind of surreal. There were these big men dressed up as babies, and when I first went to the club they were all crawling around on the floor acting like babies. So it was a very visual kind of attraction, but it also had this underlying psychological fascination. There was something going on that I couldn’t really work out. So it was not only this incredible visual opportunity, and a creative opportunity, but I also saw it as a journey, or an anthropological study almost. It took me a long time to work out that there wasn’t actually that much to work out. At the end of the day, I don’t necessarily think that it was this big psychological thing. I think it was more a fetish.

Rijs: So you don’t feel the psychological aspect could have been because they missed out on a certain level of nurturing while they were growing up?

Borland: Well at the time I felt that, and that’s how they explained it, and that’s how I identified with them because I had a lot of empathy for that, and I understood that. You know because my mother had been alcoholic and had seven kids, so I really understood the idea that they didn’t really have the mothering and a lot of them felt that they hadn’t been indulged as babies. So I really understood that, but, at the end of the day, seven years later, I began to wonder how much of that really was what it was about.

© Polly Borland, Courtesy of Murray White Room, Melbourne

Rijs: Do you think that was the beginnings of an interest in exploring fetish in your work, because looking at your current exhibition Monster there is a sort of fetish element to these works also. Can you discuss that a little bit?

Borland: I don’t think about it like that. The thing is, I’m not really interested in fetishes at all. The adult babies was one I had a particular interest in because it fed all my imagination. So there was the surreal aspect to it, there was the idea of giant babies, it was a phenomenon that I had never heard about before and few people in those days when I photographed them had really heard about. Nobody had ever really properly documented the phenomenon, so for me it was a particular fetish that I found interesting. Other fetishes, I don’t know, maybe there are some that are very unusual that I would be interested in. But I suppose what I find interesting on a visual level I don’t really on a psychological level. For me the standard kind of fetish, the BDSM thing I really am not into at all. So if you can let me know how it is fetishistic, if you can articulate this to me that would be good, because for me I don’t see it as fetishistic. I don’t see it as hinting at any kind of conventional fetish.

Rijs: There are a few things in your work that stood out to me in that way, particularly this one you have titled Gag where it appears to be featuring a woman who has an object shoved in her mouth, and a stocking pulled over her head, distorting her face. There’s a similar element in the ones you’ve titled Tits and Mother as well, and the big photograph with the red figure that was hanging on the end wall, Monster, which depicts a contorted figure in a body stocking. There seems to be a repetition of what appear to be female figures that are bound with their arms behind their back, and one where she is kneeling, bent over with her head down toward the floor. I suppose those sort of elements could be read as being fetishistic in nature.

Borland: See again, I don’t see it as fetishistic, but I feel that this work hints at violence, and probably it hints at some kind of sexual violence. Now I don’t think that other people necessarily read it like that, but the more I have gone into the gallery and seen it on the walls, I can see that on some level, when you look at the work together, it does appear that way. There is red, which obviously symbolises blood, and people are sort of shoved in body stockings and their faces are distorted.

Rijs: Now that you mention the colour red, I’ve noticed this red circle seems to be a reoccurring motif in your work, which is throughout this body of work, and even goes back as far as Bunny from 2005. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Borland: For me it is not necessarily the colour red, but the shape of the circle is literally on an aesthetic level one of my favourite shapes. I am really into organic shapes, so round feels organic. The thing is that I could try and psychoanalsye myself, and there were quite a few years that I was in therapy, but nothing that I can remember explains this work, or explains any of my work. I think that artists in a lot of cases – you know good artists – almost have second sight. What I mean by second sight is that they are very good at absorbing or kind of knowing their environment, or the broader environment. So somewhere along the line maybe I was aware of something that was quite foreboding. It feels to me that a lot of my work is kind of like that, in particular this body of work.

Rijs: One thing that did stand out immediately to me when I looked at the work was that it does have this violent undertone and the use of the colour red almost highlights that. Also the way these female figures are bound and gagged, while aesthetically pleasing to look at, it was a little bit confronting. So I was curious to understand the background of these works, and whether this sort of representation of women in your work reflects or portrays in some way your own experience as a woman.

So, I remember having very big feelings as a child. I was quite a forceful little girl. I also remember at a very young age I wanted to be a boy. I was very outspoken, and I think somewhere along the line, and I don’t think this necessarily came from my parents, but I think it came from my school environment, I was told to shut up.

Borland: Well, yeah. So, I remember having very big feelings as a child. I was quite a forceful little girl. I also remember at a very young age I wanted to be a boy. I was very outspoken, and I think somewhere along the line, and I don’t think this necessarily came from my parents, but I think it came from my school environment, I was told to shut up. I think that a lot of my work is, if I am going to psychoanalyse it, more about that. I think it’s something women are told at a very young age, you know it’s by osmosis almost.

So the violent and the sexual kind of presence, and the connotation in my work is very much metaphoric. The binding, the gagging, all of that is very much on some level about being oppressed. At some point understanding or being told that, and this can happen to boys as well. In actual fact – and you and I talked about this the other day – my son was misunderstood and basically not listened to, and not believed in a lot of ways, and luckily my husband and I listened to him and understood, because we were as culture-shocked as he was.

Rijs: Just to give this some context, this was after your move to L.A, where you’ve lived for the last six years?

Borland: Yeah, so this Monster body of work is sort of in the middle of all this, the whole journey – the six years of severe culture shock, my son being treated as an outcast, in whichever community we put him in. He was rejected even from his community that should have embraced him, because in Hollywood you are gagged – everybody’s gagged, you know. The American culture is very different, but in Los Angeles it’s even more tricky, because you’ve got the kind of shadow of the Hollywood movie industry. It’s all secrets and lies, and smoke and mirrors. So it’s very hard to get any bearing and very hard to speak the truth, because no one is speaking the truth – and they don’t want anyone speaking the truth.

… in Hollywood you are gagged – everybody’s gagged, you know.

So in a way this body of work is very indicative of what I was actually going through, which was literally being gagged and bound. But I feel like this has also been my whole life. So after six years of literal trauma, I’ve come out the other side and I now have a sense of creative, emotional, and intellectual freedom, where I can actually go ‘well I don’t give a fuck about what anyone thinks of me anymore’. Now that’s freedom. I’m not here to play the game. I’m not here to conform. I’m not here to show you what you want to be shown. I’m here to mine whatever I have inside me, and as a visual artist, to put it into whatever medium that I choose at the time, and then put it out there. And then whether people like it or not is for me kind of irrelevant.

Rijs: When we had a chat the other day you used the word cerebral when describing the way you work, saying you don’t work in a cerebral way. Can you explain what you meant by that?

Borland: Right, I’m not really very analytical about what I do, or how I do it. I do think things through, but I also work very much on an intuitive level. I gather props, and then I get whatever it is that I am going to photograph, and I create whatever it is I am photographing as I’m doing it. So there is a bit of pre-thought, but a lot of it is actually in the moment. However I have general ideas, like at the moment I’m trying to conjure mythological creatures. So yeah it’s not cerebral in the sense that it’s not very theoretical, I mean for instance I spoke to someone the other day actually – Bon Mott – and she said that most visual artists have to have a theoretical basis now in Australia and that’s why a lot of people go on to do PhDs.

This is the thing. I feel like I wasn’t taught to be an artist. I come from the school of thought that you are either an artist or you are not. And a lot of people nowadays, and for the last twenty years, are taught to be conceptual artists, but conceptualism isn’t the only language.

Rijs: True, a lot of the Australian art scene is very theory focused.

Borland: Well, where’s that going to get anyone? I don’t understand that mindset. For some people, yes, but a good understanding of art history would get you some kind of contextualising of your own work, you know, but I don’t understand why you need to be able to write a thesis in order to be able to support visual art. This is the thing. I feel like I wasn’t taught to be an artist. I come from the school of thought that you are either an artist or you are not. And a lot of people nowadays, and for the last twenty years, are taught to be conceptual artists, but conceptualism isn’t the only language. Australia is really hung up on this theoretical thing, and for me it’s like, ‘yeah, but if the work ain’t good, it ain’t good’, and it can have all the effing theory in the world. I’m not anti-intellectualism at all, or anti-knowledge, it’s just for me it can become really pretentious and kind of constraining to have a whole theoretical and philosophical basis to your work, but you know I have always in some sense worked outside the system.

Rijs: Previously I think we’ve touched a little bit on having a history of trauma, and you’ve discussed growing up and basically being silenced. Do you feel like having that trauma in your background comes out in your work, or your art practice helps you process that in some way?

Borland: I think it does help you process it, and again, I think we talked about this the other day, and work for me is therapeutic, so being creative is therapeutic. I suppose now there is a real freedom for me, because I no longer care, and I feel like I’ve got to a point where I am not afraid anymore, and I think at one point I was afraid. You know, I don’t know if I was afraid of rejection, but I think I was just afraid of people, and afraid of maybe not being liked. You know, and afraid of not being a good girl. And so probably all those things were playing into it.

Rijs: Sugar and spice and all things nice.

Borland: Yeah, and now most of the artists that I really admire are just fearless, and they literally don’t give a fuck.

Rijs: So who would be the main ones that come to mind when you say that?

Borland: Well, Mike Kelley is someone that I think is amazing. I think I only really looked at his work properly when I got to Los Angeles, when there was a retrospective. He actually killed himself. He was an extraordinary artist. His work is very varied, but incredible. I think he is a genius. And of course there is Diane Arbus – and how fearless was she? I mean she was literally walking around New York in the 50’s, 60s and 70s and going into areas and meeting people who no one had wanted to put the lens on before. So she was an anthropologist, I suppose, and non-judgmental. She wasn’t making judgment, and that was what was so great about her work.

Rijs: Yeah we can see an element of that in your adult babies series.

Borland: Yeah, so, Diane Arbus, Mike Kelley, and I am obviously very close to Tony Clark, who is an Australian painter who does mainly landscapes – and I love, love his work. I think he is extraordinary.

… most of the artists that I really admire are just fearless, and they literally don’t give a fuck.

Rijs: I’m currently looking in your book Smudge, and there is this kind of humorous, almost playful element to these works – the faces are distorted and the figures are, as you described the other day, in this genderless state, which is interesting. However, looking at your current work, exhibited in Monster, which is showing at Murray White Room at the moment, comparatively speaking, I suppose you could say they’re a lot more dark and sinister. There is a large gap between these bodies of work, so I’m wondering where this shift occurred?

Borland: Well I think that Smudge was quite playful. Every week I’d go to my friend Mark Vessey’s house who was also a photographer, and I would photograph him for a few hours once a week, and that went on for a year. And then Nick Cave – who’s a friend of mine – responded positively to the work, and he said ‘I’ll sit for you’. So he’s in some of the photos. Then to balance it out I thought I’d get my friend Sherry Lamden to model, because I didn’t have enough work of Sherry. So there are actually the photos between Nick, Mark, and Sherry. The predominant photos are of Mark. So, I think it is kind of playful, but again, I think there is a lot of male energy in Smudge, and weirdly even though you think the works in Monster are darker and more sinister, I think they are more beautiful.

Rijs: Another thing we haven’t really talked about, which I think is interesting and worth noting about this work that you currently have showing, is that many of them are tapestry works.

Borland: Right, basically because a lot of my work is also about transformation, and distortion, I think that with the tapestries it was another way of transforming and distorting. Also I love the 70s, I love those sort of artsy and crafty things. So initially it was an experiment to see how it went and then I think I have just sort of developed it as I’ve gone along, because it works. And now I’ve developed the double-sided thing, so you can hang them either way, and actually the wrong side is more interesting because it’s even more abstracted.

Rijs: Definitely, when I went to your opening the other day an exciting element of that experience was seeing these works being flipped and having that reverse side revealed, and waiting in anticipation for the next one to be flipped. It is quite a stand out feature of this body of work. And, I’m guessing, when these were made the thread was stitched into the back, so the backside is more abstracted and angular than the front, which is like this neat, pixilated image.

Borland: Yeah, and also the front side’s almost a digitised version of the photo, so it’s pixilated, because it is actually a digital pattern made from the photo. So you’ve got this Pac-Man type of way it all looks together. So, I’m developing things now even further. But I think for me it’s about altering – always constantly altering, and distorting – but also creating something that transforms the original. So it’s kind of all tied to the same ideas because, again, photographs originally were a document but very quickly they became more than a document for me. It was like my canvas, you know. It was what I could do to create the scene of the person that was in front of the camera.

So it was always about altering my reality. Always, and right from the beginning it was about the framing, it was about the light, it was about who I photographed, it was about what they were wearing, you know, every little element. Photographers are generally pretty control freakery, and I’m very control freakery, but as I’ve gone along reality is just not enough, you know, it’s just not. But I feel like, for me it’s no longer about reality, it’s about my own internal, existential kind of life.

Rijs: I can see that. I could see an element of that in these tapestries when they’re reversed and you see the underside. The front is like the neat reality you show the world, and the flipside is what’s really going on underneath.

Borland: Right, and were you there when I was talking about the dress that I had as a kid?

Rijs: No, I missed that.

Borland: Okay, because this reminds me of being in nursery school in the early sixties, when I had a dress that I used to wear to school, which had a different bit of fabric that you couldn’t see. So what I’d do is I would go up to various different parents who I knew, and I’d go ‘look, surprise’, because it was all one fabric, but when you lifted it up it was a different fabric underneath. So it was like my surprise dress, and I see these very much as like a surprise.

Rijs: They certainly do have that element of surprise.

∆

POLLY BORLAND

MONSTER

PHOTOGRAPHS AND TAPESTRIES

MURRAY WHITE ROOM, MELBOURNE

14 NOVEMBER – 21 DECEMBER 2017

and

23 JANUARY until 3 FEBRUARY 2018

POLLY BORLAND

www.pollyborland.com

Melbourne based artist, Andy Rijs has a love of colour, a passion for treasure hunting, and a playful nature, all of which have found a way into their current arts practice. Utilising commonly found, mostly plastic objects, scavenged from op-shops, recycling centres, and the artist’s own home, abstract narratives are pieced together. Rijs explores themes around gender, sexuality, and the abject body.

Andy Rijs has recently graduated from the Victorian College of the Arts, with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting. Prior to this, Rijs has been a practicing artist for a number of years. Their practice spans painting, drawing, sculpture, installation, photography, and digital media.