Know My Name, Campaign for Gender Equality

Gender equality is on the agenda. In the wake of #MeToo, #TimesUp and global Women’s Marches, the conversation about power imbalance and equality is rippling through the art world. Following on from strong initiatives by Tate Modern and the Uffizi Gallery, now the National Gallery of Australia is campaigning for women artists. Beginning with the Know My Name campaign, the National Gallery of Australia is calling for ‘equal power, equal respect, equal opportunity, and equal recognition for women artists,’ as it rolls out a program of events, new work commissions and exhibitions that put women out front.

Culture shaping and culture making have, for centuries, been heavily biased to exclude the contributions of women. In the pool of Australian contemporary artists there are a lot more women making art than men, yet men are given the majority of opportunities, have more of their work collected in state and national museums and get more representation and exhibitions across the board. According to the Countess Report 2014, ‘those graduating with degrees in fine art or visual art in 2014 were 74% female and 26% male, while those with post-graduate degrees were 75% female and 25% male’. Says Elvis Richardson of the Countess Report, ‘The closer an artist gets to money, prestige and power the more likely they are to be male’.

However, this is not just a local issue. In London, 78 per cent of galleries represent more men than women with only 5 percent having gender balance. As Tate Modern director Frances Morris has said, women have been systematically discriminated against for centuries.

Major institutions have typically failed to support the careers of women artists.

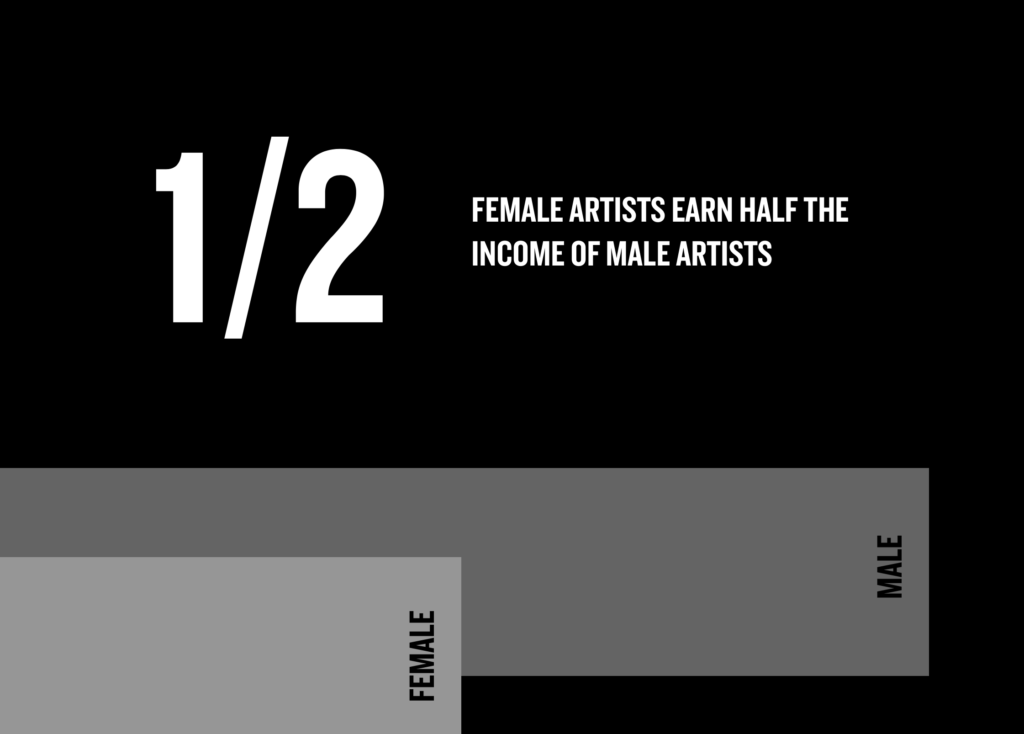

In shocking, but unsurprising, findings by an international team of researchers, (Adams, Renée B. and Kraeussl, Roman and Navone, Marco A. and Verwijmeren, Patrick, Is Gender in the Eye of the Beholder? Identifying Cultural Attitudes with Art Auction Prices , (2017), their comprehensive study revealed that works by women artists attract prices that are nearly 50% lower than those for works by men. They found the price gap for female artists was greater in countries and years with greater gender inequality and the price gap decreased as gender inequality decreased. ‘Our results reveal the struggle and cultural bias facing female artists in getting recognition and true compensation for their work,’ says Associate Professor Navone.

Recognising these unreasonable imbalances and acknowledging their own small proportion of women artists in the collection at only 25%, the National Gallery of Australia is taking action.

In this interview for Art World Women, Claire Bridge speaks with Alison Wright, Assistant Director of the National Gallery of Australia about their campaign for gender equality and cultural change.

“Women have been shaping Australian culture for more than 60,000 years and it is through the voices of artists we can define a country of acceptance, kindness and inclusion.”

Alison Wright

CB: It is exciting to see the National Gallery of Australia stepping up in the campaign for gender equality. Action by a leading institution has been long called for and eagerly awaited. How has the #knowmyname campaign come about and what is your vision for it?*

AW: The campaign came about in only the last couple of months and was born in two places. Firstly, our curatorial team came up with the idea of an exhibition that really focussed on Australian women, not just the women that we know but also the women that perhaps have not yet had the limelight or the discovery. I was taking a look at the conversation in Australia post #MeToo and I felt somewhat disappointed in the lack of diverse and complex viewpoints that look at the issue of gender and diversity. I felt the that the conversation in Australia isn’t elevated and isn’t progressive, on the whole. There are pockets of people doing really interesting things and lots of people looking to change. So it’s not a criticism of the landscape of Australia, but if you look across all of that you begin to ask, ‘Where is the real action? Where are those who are taking this issue to task and really trying to address the imbalance in gender, the lack of gender equity and diversity?’

Our results reveal the struggle and cultural bias facing female artists in getting recognition and true compensation for their work.

Marco A. Navone

I was aware of the campaign by the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington D.C. in 2016, which asked people, ‘Can you name five women artists?’ They came up with the #5womenartists campaign. My first point of call was to talk to them and to understand how that campaign has worked. One of the things they discovered was how much people are willing and wanting to share, to talk about female creative, female designers, contributors, artists and so it’s been a really fantastic experience to learn from what they’ve done.

‘Where is the real action? Where are those who are taking this issue to task and really trying to address the imbalance in gender, the lack of gender equity and diversity?’

ALISON WRIGHT

Further, we felt that the recognition of women artists in this country is certainly not a topic that is front and centre every day. We tend to focus a lot on the political atmosphere or a conflict atmosphere when we are talking about gender. There was a role that the National Gallery could play and should play in leading a progressive cultural national agenda. That has become a mission for us.

CB: You come from a diverse background and bring a wealth of experience from roles in senior management, marketing and communications, across a range of organizations, including the Grand Prix. What is your own role in this culture of change and leadership? How do you see the NGA as a leader in establishing gender parity for women artists and creatives?

AW: My role… well I don’t have a background that is entirely in the arts. I started as a journalist so perhaps my heightened awareness around curiosity, asking questions, thinking about things from other viewpoints is the foundation of my career. Obviously and absolutely I think that role the Arts play in all art forms in building a life, a cultural life and not just a cultural life, but a life, is an incredibly important part of our world. How we intend to step up as leaders is through this project. We see this as the first of many initiatives that we will take in addressing imbalance.

We have taken a look at the collection and as you might have seen, we are talking about our Australian art collection having only 25 per cent women representation. There are some caveats around that, for instance in our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collection it is more around 35%, but if you look at the totality it is 25%.

I think one of the ways that we can take a leadership role is to be part of a conversation, to lead a conversation but to not always be perfect. I mean if our representation was 70% female, is it right that we take a place in society saying, ‘Be like us. Follow our lead?’. (see editor’s note*)

”We made the assessment that we need to improve our holdings of women artists… We made the decision to do it under scrutiny and to bring everyone with us and, in doing so, encourage other [galleries] to do so, lead a discussion and . . . lead in the representation of women in our holdings, our collection, in our programs. We’re doing that because we believe we’ve not done a good job so far.”

Nick Mitzevich

I think actually there is a lot of humility in an organisation, that is the leading and premier visual arts organisation in the country with the largest collection worth 6 billion dollars, taking a position and saying, ‘We’ve got some things we want to address. Come on the journey with us in terms of discussing this issue.’

I feel that’s a value that we hold quite high here. There needs to be humility in this discussion. And the discussion is going to change and evolve. We are going to do different things.

But one thing we have promised ourselves as an organisation is that we are not just going to have one exhibition and say, ‘There we go! We did a lovely campaign…’

“We want to do more than have a conversation about equality, we want to take action and address the significant imbalance before us… The value of women artists in this country needs to be elevated as we are a thriving, diverse culture that should be celebrated.”

Nick Mitzevich

CB: It’s certainly heartening that you are all approaching this with a willingness to bring in a diversity of voices and other perspectives in order to open up this important conversation.

AW: The issue is complex and changing and has many voices contributing to it. The last thing the National Gallery wants to do is sit on top of the mountain and preach. We’ve got to be talking with everyone else about what change looks like.

The campaign is born in the spirit of a partnership model. What normally happens in larger arts organisations is that the exhibition gets decided, it gets launched and there is a marketing campaign that goes with it. What we have done here is put the idea #knowmyname at the heart of the campaign and build everything around it. But at each point that we are building, be that the social media component, it is in partnership with Instagram and Facebook. The research part of it is in partnership with the Countess Report. At every point, one of the things we want to do is to collaborate, with those that have already begun work and we are building on the work that they have done, like the Sheila Foundation or NAVA or the NMWA in Washington

And we are looking to take partners that are going to broaden the reach of Australian women artists. So, one of the initiatives we are talking about at the moment is a really massive outdoor billboard campaign where we are putting women artists across the country. Now we are still in planning for that so we haven’t announced it but it’s kind of indicative of the thinking around each of the initiatives we’ve got in terms of the theme. It’s got to be in collaboration with people.

I think the days of museums and galleries stepping out and having a single voice are over because it doesn’t encapsulate how we all actually work. We work in a collaborative way.

CB: With arts funding consistently cut over recent years, in particular further diminishing of the funding and resources available to women artists, do you see that the NGA, public galleries and museums have a role in bridging that gap? We know that by having women artists in collections, that they are more likely to be curated internationally into significant museum and gallery exhibitions if they have that reputation established back at home. So the question is twofold.

AW: On the commission front working with contemporary women artists is absolutely critical and making that a focus for the organisation is something that we are doing. Commissions take time and we have announced that we are working on a commission with Patricia Piccinini on a new major work that will be unveiled in March of next year, as part of the Balnaves Contemporary Intervention series. This year’s Venice Biennale artist, Angelica Mesiti, will be bringing back her 2019 Venice Biennale work, Assembly to be shown in the gallery.

These are the international moments where the light is shining on an Australian woman artist. We really have to make sure that we are doing that back here, where people know they can see and come to experience the artwork of these significant artists.

The commissioning part of this campaign is really important. I know too, that in terms of contemporary acquisitions we have been heavily focussed on looking at female artists, both in Australia and internationally.

‘A person has to have the ability to step into a space and carry people with them, but they also need to say these are the right actions for the organisation, and while I appreciate there’s a portion who might disagree, this is where we stand and this is where we are going.’

ALISON WRIGHT

AW: Absolutely. This is about leadership. 100% it is about leadership. We feel comfortable saying that. This is a program and project that we feel is taking a leadership position. What is important also is to be sharing that story. There’s a reason we are talking about this in this forum and other forums. There is a reason we are making a statement and saying there is actually a focussed campaign.

CB: It is about changing culture over the long term?

AW: Absolutely, Yes. It is about changing culture. Most of the gallery professionals I know are really keen to see gender balance, diversity, inclusiveness, many voices, Indigenous language. There’s a whole lot of things that people are seeking to do, not just gender balance. I think that we just have to support each other and go and do them! I think this is a time of action and demonstrating to all Australians that we can be a progressive, inclusive, kind nation, which is something I think really comes down to leadership.

CB: What are some of the qualities and characteristics of leadership that you value?

I love to see courage inside of organizations. The room for success and the room for failure.

The room for many voices but also around really significant change. How you bring change about often requires courage. So that level of fearlessness is something I do identify with, in the way I approach projects like this. It means you’ve got to be up for criticism, open for criticism. Already people are eager to point out we are not the exemplar of gender balance. I think that in 2019, it’s okay not to be perfect. So, I approach my own leadership in that way. I’m ready to say when I don’t do something perfect. I am ready to understand….

But also to have that courage to go, “This is the conviction I want to put behind this. This is what we need to be doing now.” So we can all move forward.

Nick Mitzevich commenced as Director in July last year and started talking to the organization about what national leadership and what leading a progressive cultural agenda could mean. In many respects, this project #KnowMyName just captures that. It’s a natural thing for me to go “This is where we need to be. Look I am full of faults but I am also full of conviction on this one.” I have hit upon something that has ignited what I think change can look like. This is really compelling. I have been taken over by the vision.

Exhibitions normally take 3 – 4 years, they require thought and scholarship. So we have shifted. We have definitely changed the pace on this one. When we started speaking to partners, everyone was so encouraged.

This is an organisation which has a significant place in Australian cultural life so we have responsibility to take that importance and really put it to work.

CB: In speaking with other leaders in the arts about what needs to happen in order to bring about gender equality in our field, one of the things frequently raised is ensuring women are gaining roles on boards, established in leadership positions, as Directors of major institutions, museums and galleries, as decision makers and influencers. What is your perspective? Do you see this happening?

AW: Absolutely, gender balance and diversity balance inside boards, in leadership positions and across the organization. It is absolutely no point in having this only in leadership if it is not then lived as a value throughout the organization. I think the voices of artists, the voices of Indigenous people in Australia, the voices of women are absolutely key but at all levels when creating this dialogue. Yes, I have worked in many male dominated environments and in many areas where male dominance sits at boards or at an executive team. Here (at NGA), the recognition that balance is needed has meant that balance is achieved. We have gender balance on our executive team. Natasha Bullock from the MCA (Museum of Contemporary Art) has recently started so we have that balance. It is terrific. And the board reflects a great diversity there as well. I think that is absolutely critical.

* “I mean if our representation was 70% female, is it right that we take a place in society saying, ‘Be like us. Follow our lead?” – Alison Wright

Editor’s note: I would suggest absolutely yes! If the NGA could turn things around to have 70% women in the collection it would be an extraordinary achievement. Certainly, one that would be worth sharing whereby other organisations could benefit from such leadership in regard to strategies and approaches. At the same time, we understand that the NGA is in a privileged position of elevated status and resources, compared with other organisations. Yet, when there is suggestion of women becoming the majority in an organisation, or more emphasis given to women, discussions can turn quickly to how that might be unfair or discriminatory to men. What is unaddressed in this kind of framing are the systemic and historical losses experienced by women along with the continued acceptance of the status quo. Internationally, reparations for historical discriminations are being addressed seriously by some institutions. For example, University of Alberta academic staff have voted in favour of a deal that gives female professors pay bumps and a lump sum to address a historic gender pay gap . Further, it is well documented that in traditionally male dominated fields, where women enter those occupations, they are paid less, and where women enter those fields in greater numbers and become a majority, that those jobs then begin paying less (Asaf Levanon,Paula England, Paul Allison). The research points clearly to a gendered bias against women. This is an issue of value. Valuing women.

The conversation has barely begun on reparations for women in the arts who have endured centuries of exclusion and discriminations, wage and income loss and loss of opportunities, let alone addressing further discriminations experienced by those who are Black, Indigenous and People of Colour. What if women could occupy more space? How many years of a major focus on women would it take to begin to achieve real parity? At the moment the discussion is centred on moving towards a conversation about equality and even that is frequently met with all kinds of resistance.

The Editor acknowledges that the National Gallery of Australia are seeking to approach this discussion with humility, to open up dialogue with many and diverse contributors in collaborative partnership with representative organisations. Know My Name is an eagerly welcomed campaign to lead a national agenda for gender equality. Art World Women is looking forward to the opportunities the National Gallery of Australia are and will continue to provide to women artists and importantly to all audiences who have yet to experience the great breadth and range of women artists and our work. As has been our mission from the beginning, we look forward to seeing a true cultural shift in how women and our work are valued.

Know My Name to discover more: https://www.knowmyname.com.au