Cara-Ann Simpson, Harnessing the Northern lights

Swathing vistas of dancing light appearing holographically around the northern hemisphere, known as the Aurora Borealis are created by energetically charged particles originating in the solar winds and directed by the Earth’s magnetic fields into the high altitude atmosphere. Painting the skies in luminous spectral lights is an apt metaphor for an exhibition showcasing the work of 31 women artists. In works that are at times highly charged, vibrantly luminous and entrancingly hypnotic, the artists of ‘Northern Lights’ hail from the northern suburbs of Melbourne, linked geographically and connecting across a multitudinous range of experiences as well as a diversity of disciplines: painting, sculpture, photography, printmaking, tapestry and new media. Art World Women spoke with Cara-Ann Simpson, new media artist and Curator of ‘Northern Lights’ about the current exhibition and her own art practice.

above: Cara-Ann SIMPSON, Re-envisioning the sonicscope: Bundoora Homestead 2012

LEDs, static sticker, VT speaker, MP3 player, MDF, cables, 25.0 x 98.0cm Collection of the artist

pigment on linen on board 40.0 x 40.0 x 40.0 cm, Collection of the artist

AWW: Cara, you are a multi-disciplinary visual artist whose medium is sound and at the same time are the Curator at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre, the public art gallery of the city of Darebin, Melbourne. I’m fascinated to know more about your own art practice which sounds intriguing (pardon the pun) but firstly, can you tell us what drew you into curating?

CS: There is sometimes a fine line between curation and practice, particularly with a practice that is quite consumed by an interest in space and its representation. During my undergraduate course I fell (by accident in many ways) into a sub-major in gallery studies and I immediately saw the parallels between my practice, or the concepts I was interested in, and curating. I have long been fascinated with how exhibitions are put together and presented, so it seemed natural that I pursue this actively.

AWW: What areas and ideas you are most interested in exploring as a curator?

CS: As a public art gallery curator I am really passionate about bringing new and challenging ideas to my audience, not to alienate visitors, rather to invite them to explore new ideas in art and what constitutes art. Secondly, I am interested in the gallery space – Bundoora Homestead Art Centre is a unique building, and the gallery spaces are not the traditional ‘white cube’ spaces. This allows me to exploit it in some exhibitions – to bring the architecture forward and look at integrating artwork with the building. I don’t particularly believe in the neutral space of the gallery, preferring to view it instead as theatrical (sometimes subtly and sometimes with abandon). MONA is a great example of the gallery space as theatre – artworks are presented with drama, flair and staged gestures. I am much less decadent in my presentations, but that concept is something that still drives the way I work with the space and the exhibitions.

I am particularly interested in bringing exhibitions to audiences that are immersive, holistic and create an encompassing experience. More and more I am interested in producing ‘sensoriums’ (within my practice as well as a curator) that look at all of the senses – not just the visual.

AWW: Opening on International Women’s Day this year, Northern Lights showcases women artists working and living in the Northern suburbs of Melbourne. What is the significance of showcasing work that is distinguished by the gender of the artists?

CS: Gender is such an enormous topic and something that is incredibly personal! Certainly contextually and historically gender roles are something that has been a topic of debate and consideration for many renowned artists, and is still something incredibly valid for exploration and deconstruction.

AWW: How did the exhibition Northern Lights come together? How did you identify the artists and what guided your decision making about who to include?

CS: When the concept of Northern Lights was developed there were a few artists that immediately sprang to mind – some from the City of Darebin Art Collection and some that I had met, visited studios or knew lived or practiced in the northern suburbs. After this initial start I then began mapping the exhibition to find an array of artists with diverse backgrounds, different stages of careers, and whose practices covered multiple ideas, methods and mediums.

AWW: Bundoora Homestead is a bit of a hidden treasure in the suburbs of Melbourne. How did it become a gallery and cultural centre?

CS: Bundoora Homestead was built in 1899 as the home for John Matthew Vincent Smith and his family, a prominent identity in the horse breeding and racing industry. In 1920 the Smith family sold the property to the Commonwealth Government who then started a repatriation hospital for returned servicemen operating until 1993 when it was decommissioned. By 1995 the property was transferred to the state. Bundoora Homestead was gifted to the City of Darebin in 1997 by the state government. In 2001, with the assistance of La Trobe University and the Commonwealth Government through the Federation Fund, Darebin City Council restored Bundoora Homestead and opened it to the community as a heritage and cultural space. It was a near miss, with plans to demolish the homestead just after its decommissioning as a hospital – president of the Preston Historical Society, Merv Lia was instrumental in saving the homestead and ensuring its status as a cultural icon was kept.

AWW: Getting back to the exhibition, the diversity of artists represented in the show is breathtaking. Can you tell us about some of the main themes? For example, notions of cultural identity, be that of the artist’s own culture or the exploration of the influence, imposition or experience of another’s culture such as the works of Jacqui Stockdale and artist Kirsten Lyttle whose Maori and Pakeha heritage are literally interwoven through her work. Are there artists whose work talk to similar ideas and approach them from different viewpoints?

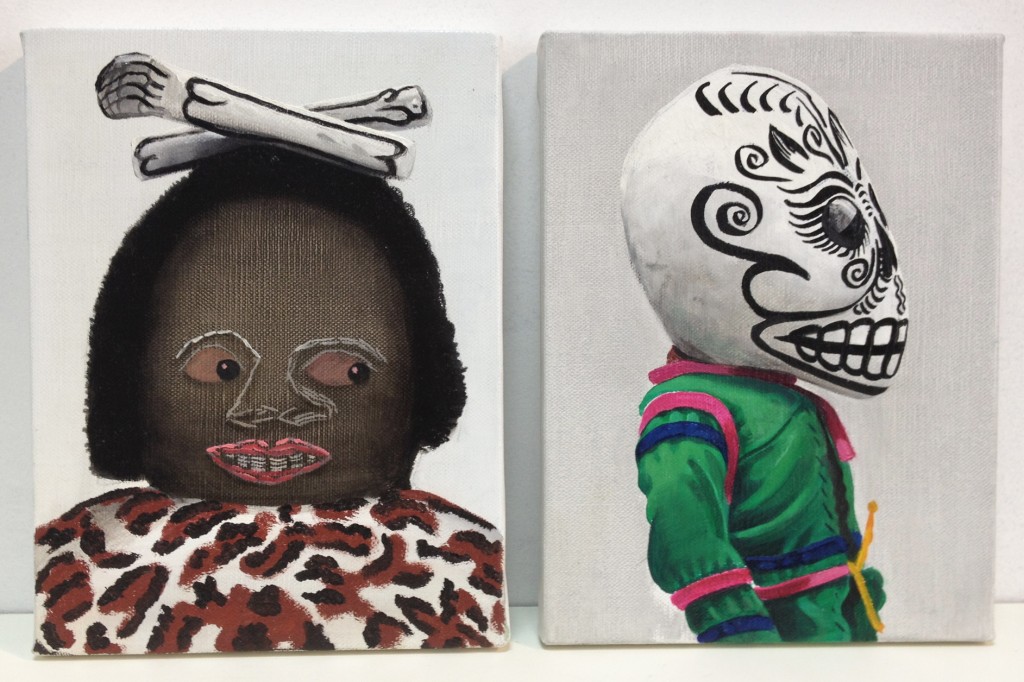

CS: Northern Lights is an exhibition where the artists are primarily connected through gender and geography, however sub-themes developed within the exhibition including the landscape and its human intervention, consumerism, interior explorations and characterisation. Stockdale’s practice engages with notions of cultural identity, often through masquerade, ritual and symbolism, although (in this work) it is presented as a survey of others identities. This idea of cultural identity is strongly demonstrated in Lyttle’s practice, which is concerned with her ancestry and the concept of saleable culture.

AWW: Representations of identity feature in the photographic works of Rebecca Mayo, Clare Rae and Justine Khamara, ranging from the personal to the global and universal, even verging on the territories of madness in the work of Rae. What relationships do you see in these works?

CS: Identity is a complex idea and in Mayo, Rae and Khamara’s work are three very different approaches using photographic mediums. There is a strong performative element in all three artists’ practices – Rae’s work often explores her body’s interaction within a site; Mayo’s series details sense of self through synergy between garments and an awareness of the body in space; and Khamara’s work is an incredibly in depth investigation of subject that is almost scientific where the subject is required to move or shift in very precise movements.

pigment ink print edition of 8 105.0 x 105.0 cm ,City of Darebin art collection

AWW: Polixeni Papapetrou, Elaine Williams and Jessi Wong explore relationship with land and country and even the planet from very different view points. Brought together these works seem to ask us to consider where have we come from, where are we now and where are we going, from unique experience. What is your take on their work in the context of this exhibition?

CS: These three artists offer very different perspectives on identity in the landscape as a reflection of the past, present and future. Elaine Williams’ work speaks of the importance of tradition and land in Indigenous cultures and how this assists in the make-up of cultural identity and sense of self, within the context of Northern Lights we are presented with a powerful and colourful sense of self through understanding and appreciating the past as a relationship between people and land. Polixeni Papapetrou’s work alternatively speaks more to the present sense of self, a transitional moment captured in an individual’s lifespan where the person is inextricably drawn into the landscape as it becomes part of their understanding of self. Jessi Wong’s stunning woodblock prints with pen question this idea on a much larger scale, themed futuristically they investigate collective identity of a culture and its changing relationship to physical environment – in this case planetary migration!

AWW: Bundoora Homestead also has Polixeni Papapetrou’s work in the collection. Being one of Australia’s more renowned artists and one who has created a platform for her work on the world stage, how do you read the significance of her work, which can be both direct and hard-hitting as well as possessing a sense of meditative evocation?

CS: Polixeni Papapetrou is an incredible artist; her body of work is very powerful and consistently of an exceptional standard. Papapetrou dissects identity with precision, her images are meticulously composed, stilled in natural environment settings, hypnotic and enduring, the performer caught in the act but aware of the watcher viewing these transitional moments and seeming to pause to enable meditation of the scene and the moment.

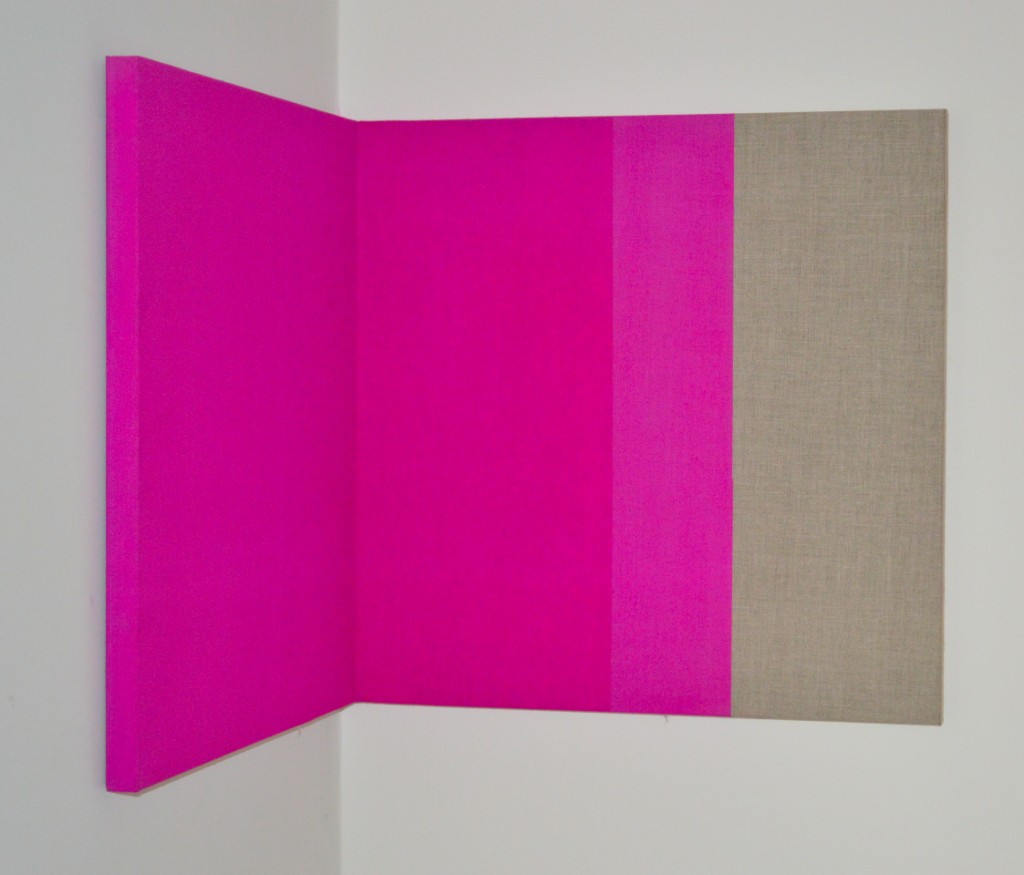

AWW: The artist who seems to stand on her own in a distinctively unique position is Louise Blyton with her reductive minimalist sculptural paintings that interact with the architecture in which they are placed. What are your perceptions of Blyton’s work and how do you see this genre of work in the Australian and broader international contexts?

CS: Reductive art is something that seems to be slow in gaining a broad audience and popularity in Australia. Certainly it seems far more accepted and popular in Europe and America where there are a few big institutions that focus on reductive and non-objective practices. Blyton’s work is exemplary in the field of reductive practice. Her investigation into material and form is incredibly refined and thorough. There are layers of meaning in understanding Blyton’s work from the artwork as object and material, to the object as integrated into architecture. These seemingly simple ideas are deep and question the art object and the art institution.

AWW: Can you tell us more about your own practice as an interdisciplinary multi-media artist? How does a visual artist make the leap into sound based work?

CS: I studied a Bachelor of Visual Arts at the University of Southern Queensland – however, growing up music was my key area of interest and talent (I actually never considered myself particularly talented or ‘good’ at art as a school subject). When I started my degree I immediately became very interested in conceptual art and the idea of immersive installation; with a background in music it seemed an easy bridge to connect the two.

The big turning point however, was when I decided to make a homage to Robert Morris’ Box with sound of its own making (1961) by sound recording myself painting different coloured monochromatic paintings and putting this into the paintings. From there I worked more and more with sound as the environmental noises in the recordings took on more importance.

AWW: You explore sound, touch, vision, even our perception of how we experience sensation itself in work such as “Resonations#1” and more recently “ Cloudy Sensoria “. What are the areas that you most want to explore through your work? What do you want the audience to understand and experience?

CS: I suspect that the direction I am currently heading in is the idea of ‘art as experience,’ but one of the dominant themes in my work has been about current trends in listening and hearing in society. I am interested in how this has changed since the invention of portable music players and their proliferation which has meant we can now control our aural experience of the world, customise it, make it have a movie soundtrack! When translating this into my artwork I bring environmental noises to the fore and look to share their beauty and intrigue with audiences. A key series in my practice has been the development of ‘Spectral Photographs,’ which combine photography with aural visual analysis of the site photographed, sometimes with sound built into the artwork as well.

This series allowed me to see my practice in a different way, and is something I think that can be more accessible and easier to understand than some of my more complex installation works. I want the audience to see beauty in our environmental sounds, and also question their own listening practices – are they constantly attached to a stream of music in the world that stops them from interacting with their environment or other people?

AWW: You have been the recipient of a number of major grants and awards including New Work (Media Arts) Music Board Grant from the Australia Council for the Arts and an International Program: Cultural Exchange Grant from Arts Victoria. Can you tell us about those projects and what advice can you share for other artists about how to approach writing a successful grant application?

CS: Both of these grants supported a major interactive installation, Geo Sound Helmets. I produced this installation with a technical team – James Laird (technical advisor, biomedical engineer), Ben Landau (industrial designer) and Eva Cheng (DSP & research engineer). The installation is a series of immersive personal sound environments based on the aural geography of specific locations. Participants are able to control the audio by changing their breathing patterns and moving their head and shoulders within the ‘helmet’ objects (they’re quite large). I wanted to create a very accessible interactive installation investigating new technologies, the place of environmental sound in society, and interactivity through biological responses.

In terms of funding, I found mentorship assistance with Artsupport (a branch of Australia Council for the Arts. Artsupport merged with ABaF in 2012 and is now Creative Partnerships Australia. One integral aspect of writing funding applications for me is to talk with the relevant departments – find out what their current visions are, will the project fit and how do I write about the project to make it clear it is well within their funding objectives.

AWW: What is your next project?

I mentioned the term ‘sensorium’ earlier. This is where I’m looking to take my practice over the next few years. I knew this was a direction I wanted to take my practice. I aim to create immersive environments that encompass all of the senses – to create a ‘seat of sensation’.

For more information go to Cara-Ann Simpson: http://www.caraannsimpson.com

or contact Cara by email: cara [at] caraannsimpson.com

Northern Lights at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre until May 5th

digital image Collection of the artist