Carnival or Culture in the art of Jacqui Stockdale

Artist Jacqui Stockdale explores the enigma that is the diversity of humanity in works that mask and unmask our cultural mores, belief systems, superstitions, rituals, identity and means of belonging. Whether intentional or not, Stockdale’s art brings forward a sense of both childlike play and deep symbolic mysticism, as if her works themselves can transform into totemic objects of reverence. Ever present are the questions and curiosities, the explorations and ethics of her foray into the many and diverse cultures of our planet and yet through her eyes and hands we get a glimpse of something at the core of a multifaceted humanity.

image above: Jacqui Stockdale, Crudellia de Mon Botanica, 2013, Type C Print, 100 x 78cm

AWW: Your work explores many diverse cultures, with anthropological zeal for a feast of humanity. Are there particular things you are saying about specific cultures? Are there particular cultures you are attracted to and why?

JS: I’d say that most of us are intrigued by humankind and the scientific study of humanity, hence, anthropology. Every human being is related to one other and we are forever repelled or attracted by the differences. I’m drawn to cultures where ritual, ceremony and carnivale play an integral part in daily life and I am also interested in how the modern world impacts on these traditions. I have spent time observing a diversity of cultures in Mexico, Spain, Indonesia, India and in Arnhem Land, Darwin and Balgo in Australia. Just recently in I made a short trip to Ubud, Indonesia. Hindu Bali has its very own unique take on life (and death) and even in the predominantly Hindu Indian sub-continent, there is nothing quite like it. Just like Bali’s famed dance dramas, its origins date back to the mythical times of gods, evil spirits, witches and bizarre superheroes. This year, I will be returning to Bali with my son for a month to make some photos and spend time observing and interacting.

AWW: Your work often uses the mask. What meaning does the mask have for you as a symbol and what function does it perform throughout the work itself?

JS: My interest in masks began during my first overseas trip to India when I was 24 years old. I found a whole street in New Delhi that specialized in costumes of Hindu Deities and I ended up with two big boxes of Hanuman, Kali, devil and animal masks with the intention of using them in my cabaret performances. This led to taking spontaneous photos of friends in masquerade. It was 10 years later that I created photographs as more serious artworks.

I’m fascinated with particular kinds of masks; usually those that are paper Mache or wood and are hand-painted and designed to be worn in dances, carnivals and festivals. I’m not that keen on making my own masks, I like that a mask comes with its own ‘’life force’ and then I play around with it in an entirely new context.

The meaning of a mask changes depending on how I use it and who is wearing it. For example: a devil mask can look menacing, cheeky or funny, depending on the way I arrange it. I see masks, not necessarily as disguise but as a way to add more to a character, or to transform from’ the ordinary’ to ‘the extraordinary’. If I gave you a mask to wear you would take on the character somehow, even for a short moment.

AWW: Multi-disciplinary is a term used to describe your art practice. You move fluidly from photography to drawing to painting and even dabble in carnival and performance, Often you combine all of these elements in the making of a work! Does a particular mode of working draw you to it more seductively, for instance photography, or does the work itself tell you how it needs to be made and directs how you will approach it?

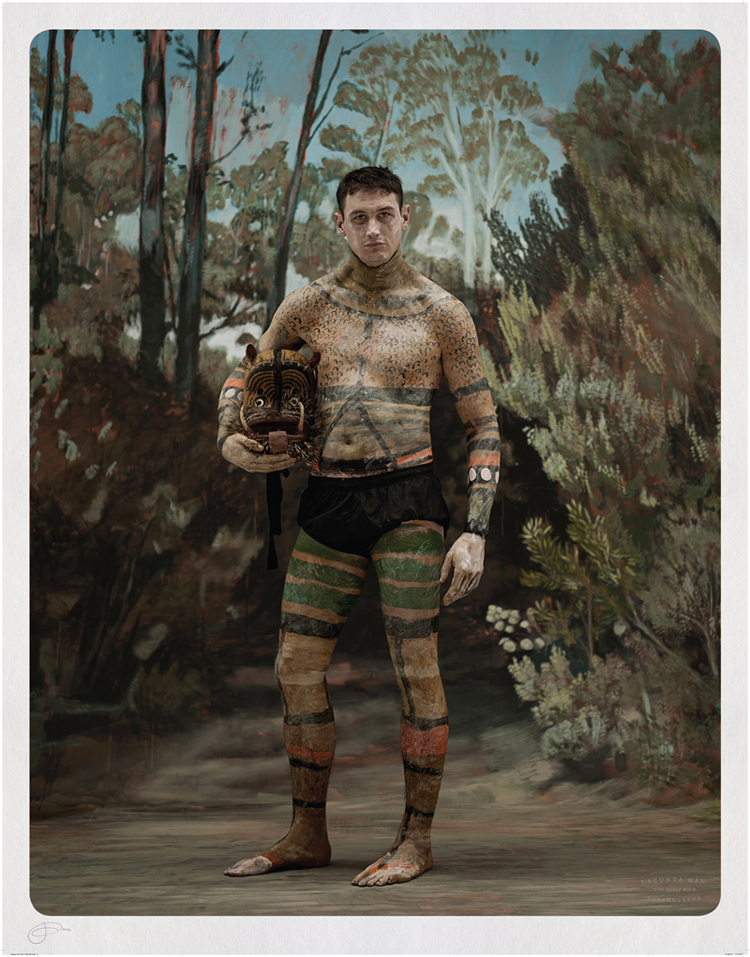

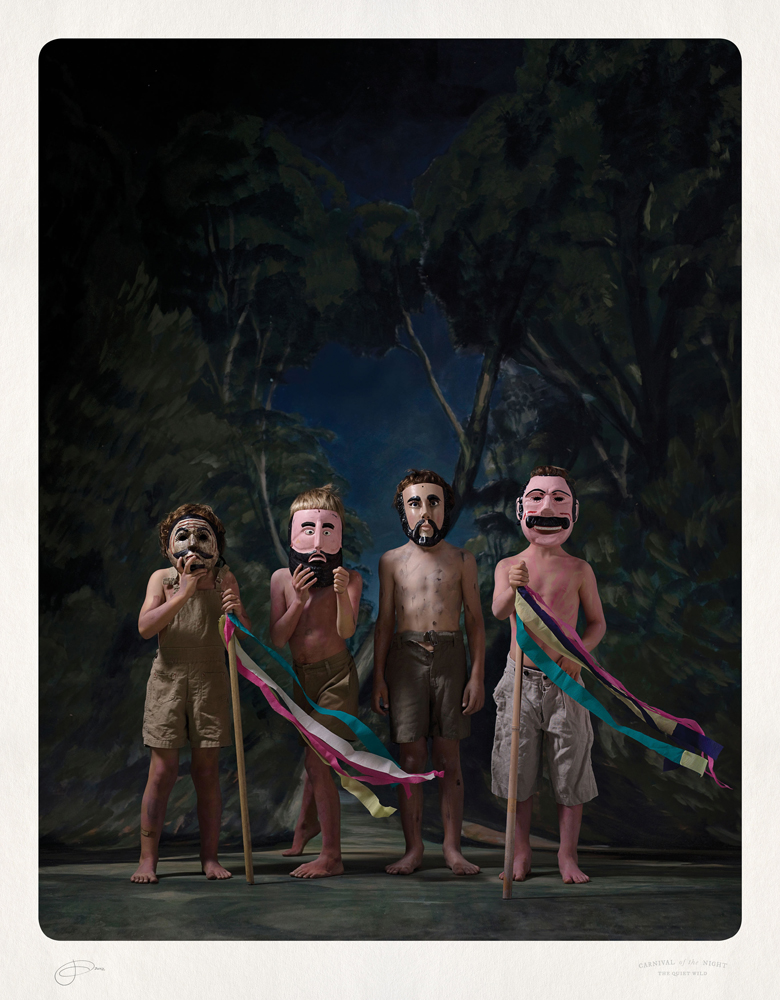

JS: I think it is natural for most artists to work in a range of disciplines, especially after making art for several decades. My early years were focused on painting and drawing directly from the human figure and this gave me a very strong foundation. Yes, I dabbled in cabaret and pantomime and ended up being gonged on Red Faces, with a duo act called, The Double Duchess of Van Diemonia. Collage came into my work while I was living in Darwin where I found it too humid to use oils. Photography has been there all along as an aide to making work, however more recently I have used it directly in exhibitions. In some work I have combined all these elements, For example, in The Quiet Wild, I made large sets, painted directly onto the body of life models, incorporated masks and used music to create a theatrical mood then photographed the model within this constructed world. This was a collage of many forms and ideas. It’s like creating a tableau vivant (living painting).

On reflection, I realise that I work with what mode seduces me at the time, though this investigation can continue for several years. Ultimately, I see myself as a portraitist working on a similar themes and I choose whatever form best suits the mood to manifest my ideas.

AWW: Plant, animal, insect, ritual, sacred site, mystery science, symbolism, mysticism and the fantastical – all take up residence in your work. You even seem to create families of characters. What is at the heart of the work for you?

JS: When I construct a picture, I automatically bring to it a range of influences, taking from my kit bag of experiences and the constant bombardment of global imagery, acquired instantly via the internet, magazines, art books, advertising, etc. My invented characters often go beyond the human form and enter the realm of the supernatural, animal forms and abstract shapes and patterns. I often form a group of characters so they are read as one entity. See the collage sculptures in The Procession, 2013.

What is at the heart of my work? Day-to-day events affect my feelings and influence my work. I am continually refining, learning and processing the barrage of visual and aural, stimulation and information Maybe I am trying to find out what is at the heart of ‘humanity’. I tend to make work based on a feeling and then let it speak to me. I’m forever inventing a character or personality, so the face is important. Most of my faces have a similar gaze, check it out, it is as if the characters are looking back at the audience, forming a two-way dialogue. Perhaps, it’s an investigation of people, a search for meaning, an unravelling of who I am or a lament to a fast diminishing loss of the spiritual, of what binds us to the earth and each other. Maybe it’s an investigation into what lies at the ‘heart’ of humanity.

AWW: Science and spirituality are the themes that recur through your work. How do these intersect for you and in your art?

JS: As I mentioned before, I am fascinated with the way science has represented cultural differences over the past century and a half. In particular, I’m drawn to the way anthropology has sought to represent physical differences between human societies. Spirituality is the balance to this; it is what we discover if we go deeper into the human experience. They both form parallels and parodoxes and appear naturally in my work.

AWW: Language – from Latin to French to Spanish – you have cross-cultural borders with the symbolic imagery and the titles you assign. The titles of your works even have scientific names. How do you choose your titles and the language?

JS: My multi-language titles draw on the way Western science regarded traditional societies as ‘the other’ particularly in early exotic postcards and photographs. I am also drawn to Barnum and Bailey circus, sideshow personalities. And, do you remember the infamous children’s book, called, The Coles Funny Picture Book, where E.W. Cole include his manifesto on The Coming Federation of the World. This has always intrigued me and given me permission to make fun titles.

As I construct fictional characters from various diverse sources, I match them with cut and paste titles. In some of my more recent portraits from The Quiet Wild, I have reverted to the original peoples’ local name rather than the introduced Anglo-centric description. Examples include Tasmanian Aboriginal names for Leawuleena (Cradle Mountain region) and Lagunta (Tasmanian Tiger) as well as Rama Jarra (Jaara Jaara) language and for the traditional owners of Victoria’s Bendigo region, a place where my mother now lives.

AWW: What is cultural identity? What does it mean for a culture to retain its distinct identity? In an increasingly globalised world, which in this age of Internet is becoming a borderless world, how do you feel about cross-fertilisation? Is the world becoming more homogenous? What are your thoughts on cultural distinctness as a structure for the future of humanity and the planet?

JS: These are big questions. I suppose cultural identity for me means how people identify themselves within a society and within ethnic, socio economic and gender varieties. I like to invent characters that blur these boundaries, becoming mixing pots of gender, age, background, belief systems, etc.

For a culture to retain its distinct identity within an increasingly globalised world is difficult and has had tragic consequences, mainly felt by minority groups. I think most traditional cultures have become disempowered, as their belief systems, language and customs that have been in place for thousands of years are no longer relevant or respected or need a major restructuring in order to survive. I remember, while living in Darwin, NT, hearing of a group of elders from Groote Eylandt that had given up passing on their knowledge as the community was no longer able to carry on in the old ways. During this time, I was working as the art teacher at the Darwin Correctional Centre, where men and women from all over the Top end and as far as Indonesia were incarcerated. The main theme that came through in the paintings that they produced there was the clash between ‘white fella’ law and ‘traditional law’. This treatment of Aboriginal people is really a form of cultural genocide.

Many sacred and spiritual practices of indigenous people throughout the world has been reduced to a form of entertainment for tourists. In fewer cases new technologies a renewed interest in ‘traditional practices’ has allowed some cultures to retain or to document language and tradition.

We are fast becoming a monoculture. We, in the first world (and I am no exception), are able to waltz in to poorer but culturally rich countries for a holiday and return laden with ‘exotic’ local products and souvenirs. We crave authenticity but don’t want to pay the price for it. I hope I am more sensitive to people and like to think that in return the work I produced may be a positive contribution to the world.

AWW: What are you telling us about human nature?

JS: What keeps coming through my work is the cross-pollination of ideas and peoples. Yet, I think my personal search is about what connects and transforms us, what is lost and what remains sacred.

AWW: In The Quiet Wild you have set up scenes, complete with painted sets, make up, masks, models and lighting and created stunning photographs, which feel historically significant. Your models inhabit characters and yet are like the photos of anthropologists of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Can you share with us about your process?

JS: There are many examples throughout history where artists have constructed their own reality, where they have used a particular format to present the human subject within a specific context to tell a story. European portraiture, generally commissioned by wealthy patrons and early photographic portraits present the human subject within a constructed scene. Photography and commercial printing made it easier to generate multiple images around the world and people started to see how other cultures appeared. I attracted to these images and employ similar formats to create my very own, Theatre of the World.

AWW: How do you set up the scenarios? Do you paint the sets first? Do you source your models first? Is the photography shoot done all at once or over a short period or do you work on each piece separately to completion before moving on?

For, The Quiet Wild, I developed the concept based on Mexican Carnivals where masquerade and painted bodies are used as part of dance and ceremony. I have a collection of original Mexican dance masks and they became the starting point for most of the characters. I made drawings, sourced models and costumes and travelled around Victoria and Tasmania to find scenes for a set of large painted Australia landscapes.

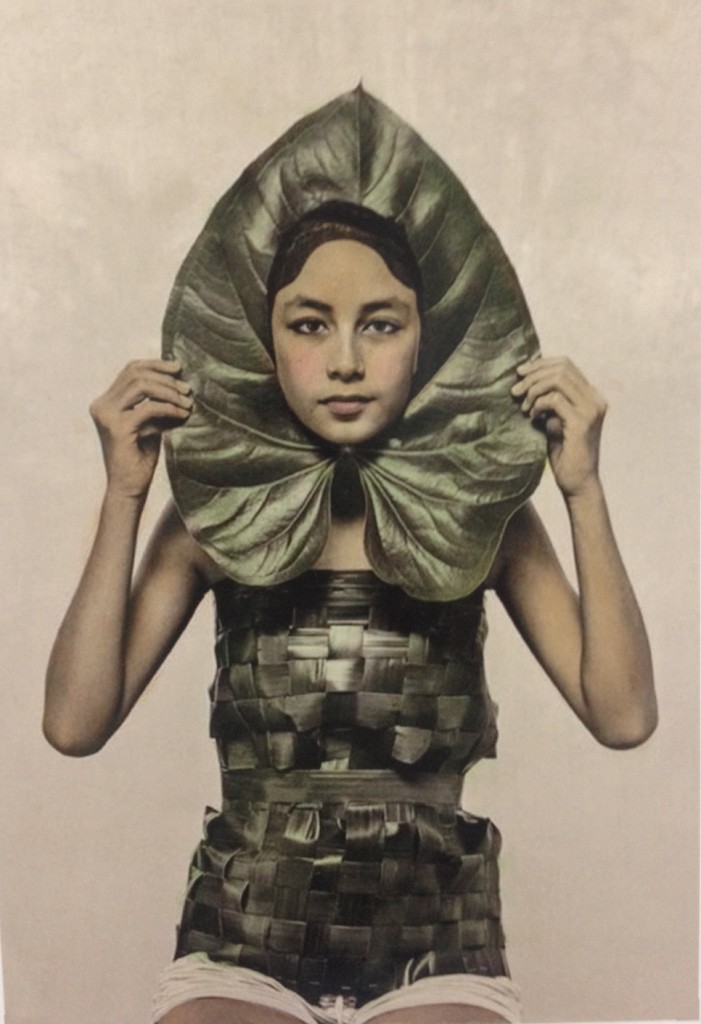

With new work, I usually begin by making half a dozen portraits based on planned characters and then allow the process of time and discovery to determine the rest of the series. As an example, while waiting for the model to show up for a photo shoot, I spontaneously turned to my young assistant and asked her to put a fluffy dog on her head, wear a costume and hold a weapon, within a few hours we had created a new portrait titled, Crudellia de Mon Botanica.

AWW: Can you tell us about your upcoming Barcelona residency? My mouth is watering at the thought of tapas!

JS: At the start of the European summer in 2014 I will be taking my family to spend three months in Barcelona to research Spanish festivals. My study will involve overnight trips to numerous festivals in surrounding regions, such as Moors and Christianos, Semana Santa, Carnivale, Penjada Del Ruc (Hanging of the Donkey), El Zampanzar,(Festival of St Fat Belly); Dia Del Traje,(Costume Day) and La Endiablada,(Festival of the Bewitched).

AWW: Which women artists are you inspired by or have influenced you as an artist?

JS: Pina Bausch, Sally Smart, Chevilla Vargas, Meret Oppenheim, Louise Bourgeois, Polly Borland, Marina Abramovic, Joy Hester.

AWW: What are your plans for the future? What are you excited about?

JS: My plans are to become more fluent in Spanish. I’m excited about finishing the next set of images. I know artists are meant to be Zen like and enjoy the process of making; something I do mostly, but it can be daunting.

For the past year, Ive been working on SUPER NATURALE, a series of close up photographic portraits of people wearing masquerade and headresses, where some of the costumes are made from leaves and flowers from a tropical garden where I was staying in Ubud, Bali. This new work is inspired by the super natural, halloween, she-devils, bunyips and horned angels,. I initially set out to Bali to study research an aspect of Balinese Hindu spirituality that openly acknowledges the duality of good/evil, negative/positive forces in human nature. In the short amount of time that I spent there, I decided to focus on what was in my immediate surroundings; my new Javanese friend and her two teenagers daughters that lived next door. The garden became my studio and the foliage the wardrobe. I made many portraits there after of other local children and their parents, finding more great props from the local market, cheap super hero costumes and ritual flowers.

While I was in Ubud for the six weeks I designed a set of elaborate mahogany picture frames for each photograph, hand crafted by local wood carvers, for whom the village is known for. I based the designs on flowers and plants with super naturale properties such as belladonna and wild arum.

Following this trip I traveled to Nashville, USA where my brother lives, it was during halloween so greatly inspired, I made more portraits and collected new masks. All up I worked at three different locations, Melbourne, Australia; Bali, Indonesia and Nashville, USA

In this work, I have replaced hand painted scenes of Australian landscapes used as backdrops for the photographs with simple sets, focusing instead on the face and textures of skin and fabric. Each life size portrait photograph is hand coloured using a combination of traditional and more recent techniques to accomodate digital papers and new fluro and metallic oil based pigments. Although it is a very involved process, I have done this as an attempt to replicate the nostalgic and seductive quality of early hand painted photography that I find so alluring and impossible to do with computer technology. Also, as a painter, I need an element of the work to be hand touched.

Super Naturale runs from 1- 29 March, 2014. This will be the first exhibition for Helen Gory Galerie‘s exciting new venue in Gertrude St, Fitzroy which also houses the Dianne Tanzer Gallery.

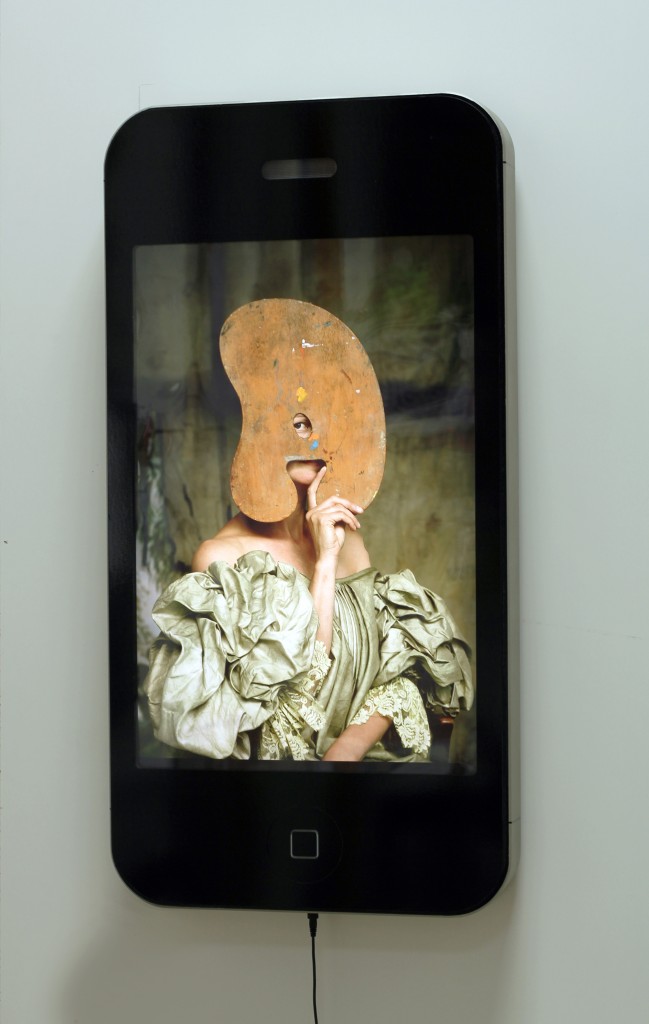

AWW: You were recently invited to submit a work for the 2013 National Portrait Self-Portrait Award at the University in Queensland and you made yours a “Selfie”?

JS: Yes. After I told my mother about the invitation, she said, ‘I hope you won’t be wearing a mask.’ I laughed. ‘It’s just that I like your face’, she said.

So great to hear that Jacqui Stockdale has joined you Edwina Corlette!