Embracing the taboo of being an artist mother

Four women artists have been drawn together spontaneously in a group exhibition “… and then there were five” showing in Melbourne at fortyfivedownstairs. Each are successful artists in their own right and each one are mothers. Their work employs diverse media such as; oil and inks through a printmaking process, figurative realism in oil paintings and the residues of performance in photographs and installation works. Even though they have worked completely independently, there are common threads and intersections in these artists’ work, surprisingly using similar motifs in the way they obscure faces and identities or even in the closed eyes of children in their images. Claire Bridge spoke with Celeste Chandler, Erika Gofton, Ilona Nelson and Sharon Billinge about art, love, the creative process, finding the freedom in the work and the (unbelievably still) taboo topic of being an artist mother in this interview for Art World Women.

ILONA NELSON

AWW: The title for this show is pretty enigmatic. There are four of you and yet the title suggests more, like something growing. What is this about?

IN: I enjoy coming up with titles and the titles I give my works don’t tell the complete story as I want to encourage the audience to interact and become a part of the art by asking questions, reflecting, and starting conversations. The title, “…and then there were five”, just popped into my head and it seemed to fit our work. It contains an element of intrigue, plus it also refers to the number of children we have between us.

AWW: How did you come together as a group? How did this exhibition come about?

IN: An opportunity opened up when an international artist couldn’t deliver their work to the gallery, fortyfivedownstairs, in time. I was invited by Abby Storey, the gallery manager, to step in and put forward a show. Erika is a great friend of mine and I asked her (well, demanded), she asked her friend Celeste. Celeste is friends with Sharon plus Sharon and Erika were represented at a Melbourne gallery together. Even though the way we came together was a little disjointed, our practices really complement each other and there are many common threads running through all our works. We’ve really enjoyed working with each other and hope to do more projects together in the future.

AWW: There is sense of play and naiveté in your work that asks us to question how we step into the world. Even in the installation of the work, coloured confetti spills out like the remnants of a party. Tell us more about fun in the making and message of your work.

IN: I have SO much fun creating and I definitely think art doesn’t have to be serious all the time.

When ideas spring into my head I can visualise exactly what the piece is going to look like, I then find the dress that fits the image, book in the babysitter (aka my mum) and off I go on an adventure! These adventures see me doing all sorts of silly things in front of the camera and I’m usually having a chuckle to myself while I work.

I’ve only recently realized that the process of taking the photographs is a performance in itself, which I have come to embrace and I’m keen to see how far I can push my own physicality. Once I have shot the images it’s like the performance has finished and I don’t view it as a photograph of myself, I just see a figure in the landscape. So much so, sometimes I am surprised when people recognize me from my work. Ridiculous, I know!

I’m interested in creating work that is more than a photograph and really pushing the limits of what a photograph is perceived to be. Even though I work predominately with photography I consider myself a new media artist as I incorporate performance, film and installation, and sometimes alter the photographs by drawing on and sewing into them. Thematically I explore identity of self and society, and try to capture the physicality of the passing of time.

AWW: Obscuring the face, hiding the head, revealing the feet; these themes of obscuring and revealing are echoed in the work of Celeste Chandler also. What do the feet tell us that the head and face do not?

IN: To be honest I work by instinct and it was only when I had finished the series and looked at the final images that I realized that all the faces were obscured in some way. But just like the titles I don’t want to be blatantly obvious and tell people what to think. I like to retain an element of uncertainty as it creates questions which (I hope) makes my work accessible and allows the audience to discover their own connections within the imagery.

AWW: The image “You swept me off your feet” reminds me of Polly Borland’s man babies. There is an innocence that is overlaid with something other, just as the dirt layers the soles of the feet. You have made this work into a pouffe which invites an interaction with the viewer – an invitation to be accepted or ignored. Can you tell us more about this work and how it changes in its different incarnations?

IN: I shot this piece by kneeling on the floor, twisting around, and holding the camera over my shoulder so it ended up becoming a performance piece as well as a photograph. I love the layers of contrast of the skin against the dirt against the delicate dress against the industrial building. I made it into a pouffe so the audience could sit down, put their feet up and enjoy the show! Exhibitions can feel like a sterile environment where you need to whisper and can’t get too close to the work, I want to break those barriers.

Website: www.ilonanelson.com

Ilona Nelson is self-represented

CELESTE CHANDLER

AWW: Whilst much of the actual skin surface is obscured in these work, what is it about the human form that makes it such a recurring subject in your work?

CC: How to draw and paint the human body, and what it means to represent it, have been preoccupations since childhood. As I child I drew things over and over obsessively – hands, faces, trees, my cat (who I used to lock in my room each night so I could draw her – poor thing). I think it was a way of trying to understand not only how to draw something but also something more existential, trying to pin down the ambiguities of life. I have always been drawn to things that constantly alter and shift, that are never fixed except in an image.

I think in the simplest sense, I paint the human body because it feels good. It’s exciting to try and create a human presence and it’s a magical thing when it happens. I love how you can look at paint – this inert matter – and then see it transform into something else – skin, hair, an eyeball.

AWW: You have said, “Each painting is an act of remaking the self” by this do you mean that you are transformed in the process of painting? How are you remade by your paintings?

CC: This comment relates specifically to the recent series of paintings titled ‘lovesick’. The paintings are like failed attempts to remake my face again and again by applying a wet substance over my skin and yet the substance reveals as much as it conceals. I think of this act as a metaphor for the ways we try to change ourselves. When I consider extreme examples, such as cosmetic surgery, I think about the psychological vulnerability this reveals and the instability of self.

I use the word ‘remaking’ rather than transformation, as it emphasizes the act of changing something but does not assume that something is transformed as a result. And perhaps this is the point, we live in a time that emphasizes and celebrates the idea of remaking ourselves, improving and changing a personality or a body that is wanting, but rarely are we ever truly transformed. The result of this however, seems to be a shifting, unstable and dissatisfied sense of ourselves.

Painting, on the other hand, is a process of transformation in which dead matter transcends its base materiality and becomes coloured light, skin, breath.

How am I remade by my painting? My image is remade in the sense that the process is a continual, ongoing remaking but not in the sense that I am transformed or improved.

AWW: Obscuring and revealing are central to the experience of these paintings. If brutality and disclosure are part of the process of painting for you, how do you choose what to obscure and discern then what to reveal?

CC: In recent years I have become fascinated by the surgical transplantation of faces – which I think is a remarkable and beautiful act of humanity. Conceptually it challenges the idea and limits of self and also, I think, of beauty and authenticity. By this I mean that I find the images of face transplant recipients to have an authenticity that has been eroded from most forms of imagery since photo-shop and probably before. Formally, the images of face transplant patients revealed how the obscuring and revealing of facial features could result in an uncanny and captivating rupture in our perception and I also wanted to explore this rupture. I am not attempting to re-create facial surgery but it has definitely informed my work. The brutality in the work lies in the rupturing of the face but also, I think, in the honesty of the depiction.

Of particular interest to me is the way that the obscuring of parts of the face or body can make the revealed parts more naked, more vulnerable, more exposed and this mediation is so central to most human cultures, and particularly in regard to the female body – from the burka to the bikini! What to reveal or obscure is ultimately determined by the way the image reads and the references that are generated.

AWW: Becoming a mother recently, these images and the title “Lovesick” conjure images and sensations of the visceral intimate experience of a baby throwing up after a feed. Is there something here about the kind of love a mother has, giving over her body utterly and without judgement to the needs of her child?

CC: I don’t think the reference to motherhood is as literal as baby vomit but becoming a mum has definitely affected my practice in every way and the embodied experience of creating and mothering a baby is profoundly informing my subject matter. However, I think it’s going to take a while to ascertain just how motherhood informs my work into the future. When I was first back in the studio after my daughter was born I did think a great deal about the metaphor of drowning, so, for me personally, this is part of this series of paintings too.

AWW: Jenny Saville has explored the subject of facial and body disfigurement and surgery in her paintings. Your work also refers to disfigurement with a viscous sensuality and warmth as distinct from the confronting and at times violent coolness of Jenny Saville. What is it about these concepts of disfiguring and describing the body that interest you?

Jenny Saville is a remarkable painter. I think compassion is very important to me, humanizing rather than dehumanising.

AWW: I have to agree with you about Jenny Saville. Which women artists inspire you?

CC: Marlene Dumas and Jenny Saville have probably been the most inspiring over the years, not only for their work but also for the ambition of their practices and their unflinching exploration of female experience.

Website: www.celestechandler.com.au

Celeste Chandler is represented by Heiser Gallery, Brisbane

SHARON BILLINGE

AWW: Process seems integral to the nature and content of your work. How does the structure and discipline of your process allow for creative exploration?

SB: Setting parameters helps me to be freer with other aspects of the work. For this series I decided on the size, the media, the palette and the source images before I started making anything. I try not to overthink things and just go with what seems right at the time. Trying to actually make decisions while making the work doesn’t work for me, so now I try to take a lot of the decision making out of the process before I start. I have a drawing background and I found the move into colour very difficult because I would have to stop and think about colour mixing while I was making the work. Now I mix all the colours up and put them in pots so I can get lost in the drawing and mark making. I suppose the mono-printing technique that I use adds to this sidestepping of responsibility. Decisions become less important because you can’t completely control the outcome anyway. The process of drawing on plates, patting the paper dry, lining it all up and running it all together on the press slows everything down, you have time to turn off the nonsense in your head. I find that all that unconscious movement while your brain is only half thinking is lovely. By the time I go back to the table to paint on the plates again I’m ready to play.

AWW: Repetition of image creates an iconic presence and allows the viewer to notice details and distinctions as we compare one image to another that might never be noticed in the time it takes to glance at a single image. Is repetition itself the subject of your work? How does the act of repetition support or enhance your creative process?

SB: I am enjoying experimenting with different ways of utilising repetition in the presentation of the work to see how this can alter the reading and using with the same image over and over again is certainly vital to my current practice. However I don’t think repetition is itself the subject of my work. It’s more that the repetition within the making allows me to play around and take more risks. I make a lot of work of the same thing so I know that if I completely stuff up some of the work it doesn’t matter as there are plenty more pieces waiting in the wings. In the past I’ve really struggled with being too precious with my work. I’m drawn to work that has a feeling of being loved and laboured over but I found that as a piece of my own work progressed and became a product of hours or days or weeks it became harder and harder to change or obliterate areas. The way I work now means I can make changes without being tentative. There is a lot more joyful playing and less overworked angst.

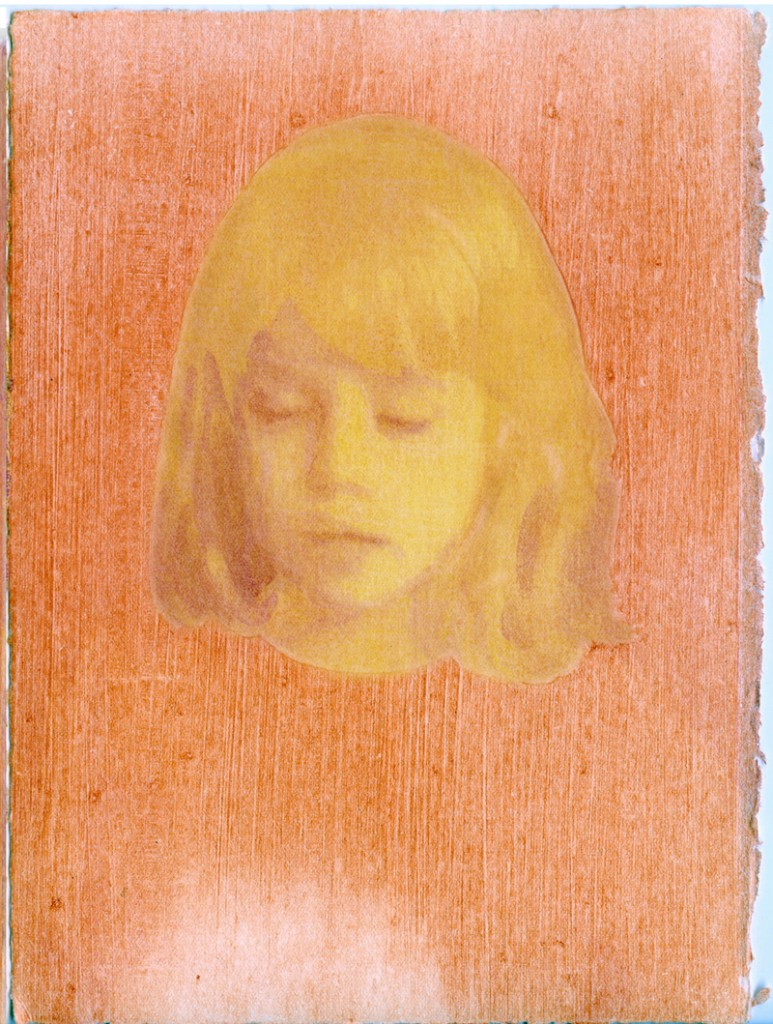

AWW: There is enigma in the ghostly after image left behind in the wake of your process. Also your subject is removed from us, her eyes are closed and we can not see what she sees. In what ways does the evocation of mystery work to engage the viewer in the substance and intention of your art work?

SB: The works in ‘and then there were five’ were developed from some mono-prints I was making of a friends little girl. In fact two of the original mono-prints are in the show. Viewers of the works remarked on the distance they felt between themselves and the girl, as if she was receding away from them. I wondered how people could be drawn to images of people who seemed to be being pulled away from that connection. I’m now structuring my Masters of Fine Arts around exploring the consequences of manipulating the distance between viewer and subject. So hopefully I’ll have a great answer to your question by the end of next year…

AWW: Each of you have an experience of motherhood that is suggested indirectly or overtly in your work. How has becoming a mother influenced your art practice, in relation to content and the pragmatics of being a practising artist?

SB: Oh blimey – that’s a biggy. I think the old saying that if you want something done give it to the busiest person you know rings very true. I make what I do count more. I mess around less and play more. I drink less tea and eat more chocolate. I remember friends telling me that having kids changes everything but I wasn’t prepared for the way it altered how I felt about everything. I don’t worry about my artwork anymore. I don’t seem to be in such a rush with it. I know I will always do it and I’m comfortable with the way the work is going. After so many years focusing on it so intently it seems hilarious that what I really needed to do was focus on something else in order to find a point of balance.

Someone said to me recently that it doesn’t seem to matter to the little girls in my work whether we are there or not. I think that’s fantastic. Before the birth of my daughter I would have struggled to justify painting children and dismissed it as too sentimental but now my world is so taken up with little girls it seems ridiculous not to paint them. I’m just making work about the biggest part of my life right now and trying to be honest about the experiences I am having. Hopefully the work goes some way into exploring the strange little creatures that children are.

Website: www.sharonbillinge.com

ERIKA GOFTON

AWW: Stillness, gentleness and attention are features of your paintings which emanate a quiet even amongst the fluttering of birds wings. Your subjects are small girls, whose eyes are closed, standing still while birds float about them. What are the birds metaphors for?

SB: The birds help me to communicate on a couple of levels. The birds allow my figures to exist in a silent, time suspended space, but they also set up a quiet tension. Will the figure open their eyes, or flinch and send the birds back into the sky? To sneak into your child’s room once they are asleep, when they are still, silent, to kiss them lightly on the cheek and to pause time, also comes with the fear and anxiety of disturbing them, breaking that silence, awakening the chaos of the day, speeding up time. That quiet pervasive threat is what really interests me.

I am also interested in how as humans we are becoming less and less trusting of our instincts particularly when it relates to our roles as mothers. Society pressures us into conforming to an ideal that makes us question what feels right, whatever that is for us as individuals. Birds represent to me an animal that relies on its instinct for its very survival and development. But I also find them fascinating because they are incredibly resilient but at the same time incredibly fragile.

AWW: Who are these young girls? You are the mother of a young son. What notions of childhood and parenting are you exploring through these paintings?

EG: Before having my son I hadn’t really considered how it would impact on my practice. I wasn’t deluded enough to think my life wouldn’t change but I wasn’t quite prepared to have my life changed irrevocably in every way. It has made me see the world and myself very differently, has made me question my sense of self and autonomy, reflect on my own childhood, and introduced thoughts and emotions I never knew I had. I have found motherhood to be many things. Joyful, isolating, tender, depressing, blissful, overwhelming, enlivening, bewildering, boring, exhilarating, confusing, guilt ridden and so much more and this work has enabled me to reflect and embody these feelings and to really tease apart, understand and make sense of my own experiences. My choice to focus on motherhood as subject matter for my artwork has not come easily and in fact at times I have felt embarrassed and apologetic for being a mother within a contemporary art context something that makes me question how far we have come as female artists. I think of Judy Chicago’s statement “I, like many women artists of my generation, believe that maternity is antithetical to the creative life, primarily because of prevailing attitudes that one couldn’t be a woman and an artist too” and wonder if much has changed?

These little girls are good friend’s children that I love dearly but because they are not my own I feel this affords me a slight distance and objectivity and also clarity to speak of my own experiences and not confuse those with the experiences of my son.

AWW: What’s it like for you finding the way to fit in your roles as artist, mother, teacher, wife, business woman etc? How do you make it work? What has helped you find the balance?

EG: In all honesty I don’t know whether I would say that I do have the balance. Unfortunately one or many of those things always seems to suffer when I focus on one or more of the others. I often feel like I have two children. One being my son and the other my arts practice. Both vital ever-changing parts of my life but both demanding of my full attention, consideration and devotion. I think the hardest thing is realising that you can’t ever give them both equal attention at the same time so there is always the feeling that one is being neglected, or is suffering. That I find extremely difficult to reconcile, but impossible to change. My husband is an incredible support too but he also gets neglected at times. We just do the best we can.

In terms of running a business, I run The Art Room where I teach adult art classes but have structured it so that the classes run only for the school terms and are mostly of a night so I can be home for my son before and after school but also so I can be in the studio during the day. It’s busy, but it works well, and I love the teaching. I have a couple of close friends who are artists and mothers and I think they have helped me to figure ways to balance better but also how to lessen the guilt that comes with the juggle. We counsel and encourage each other. Support is so incredibly important.

AWW: You have recently been awarded the Toyota Community Spirit Travel Award and will be going to PointB Worklodge in New York to undertake a month long residency in June 2013. Can you share some of your plans?

EG: The main focus is for concentrated studio time where I can disconnect from day to day responsibilities to completely focus on the work and its future direction. I am so excited about exploring, trying new things, really concentrating on the idea, making mistakes, having breakthroughs, succeeding, failing. I am really interested in exploring the potential of interdisciplinary approaches particularly in experimenting with merging elements of installation, traditional painting techniques and contemporary drawing practice to create new methods and processes. Whilst in New York I am also going to attend the Drawing Marathon at the New York Studio School to not just look at my own approach to drawing but to also gain resources that I will use on my return in organizing and running a 5 day drawing intensive at The Substation in 2013. The idea is to give artists the opportunity to work with a different artist every day that will really challenge their practice and encourage them to step way outside their comfort zone.

Erika Gofton is represented by Dickerson Gallery and Anthea Polson Art

The group exhibition “and then there were five” is showing at fortyfivedownstairs, Melbourne until Dec 22nd