The Moving Impulses of Hannah Quinlivan

Revealing the hidden architectures of societal structures that contain and restrain our emotional lives and psychological selves, Hannah Quinlivan navigates a multidimensional universe of forms and fluid temporality in her expanded drawing practice. Moving with the impulses, Claire Bridge discusses with Hannah Quinlivan the shifting flux of currents in her work.

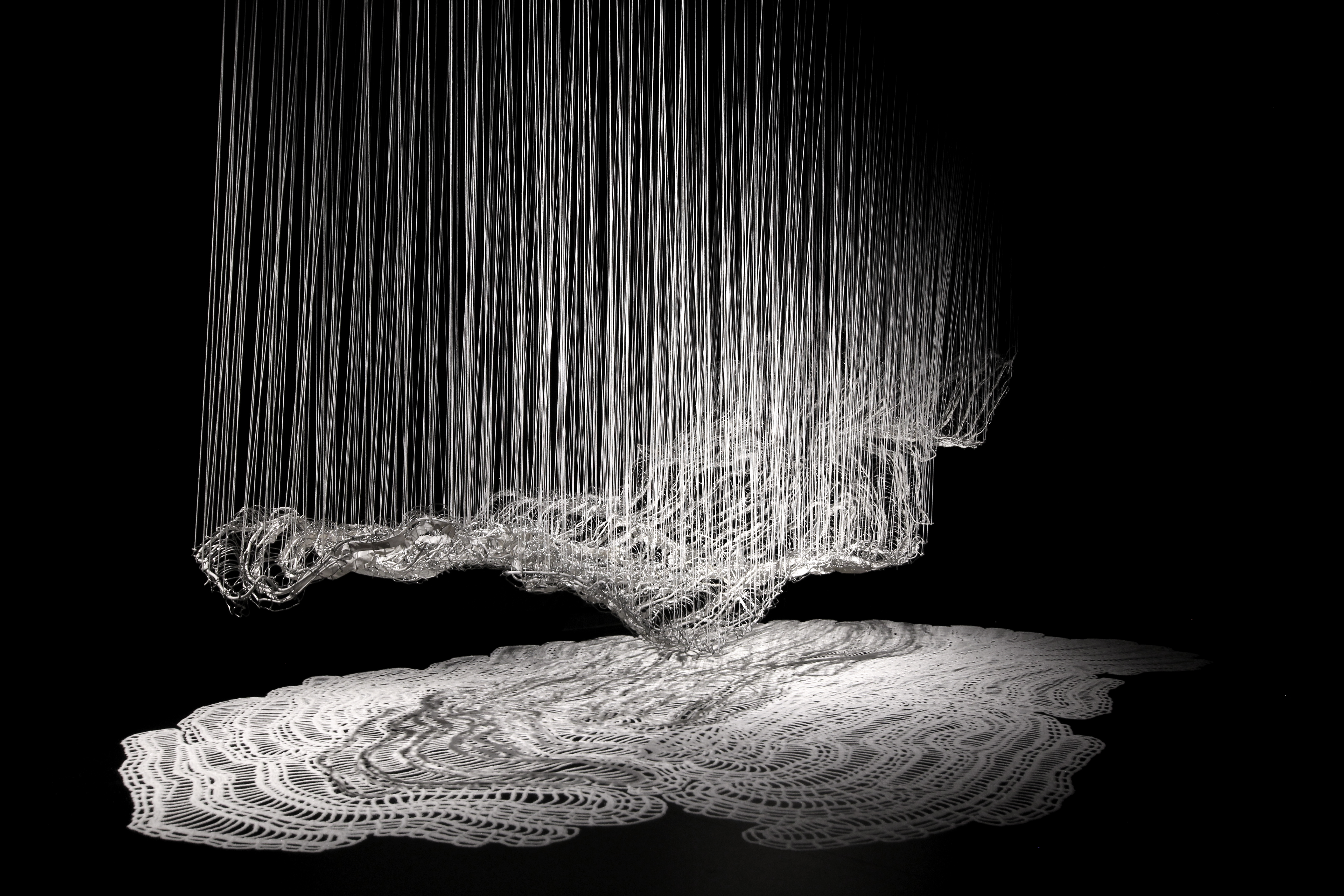

image above: Hannah Quinlivan, Pellucid, 2017. QUT Art Museum, Brisbane. Aluminium, adhesive tape, yarn, salt and shadow. 600 x 260 x 500 cm. Photograph by the artist.

CB: You speak about societal patterns and global structures as inspiration or conceptual background to your works, such as the way certain paradigms or structures either constrain and restrict or allow for flux and change. Can you tell me more about this aspect of your thinking? What are you referring to?

HQ: I guess I am interested in the way that the architecture of our emotions is shared among people who are otherwise disconnected. We tend to think of emotions as something intensely personal and individual. Yet often our moods and habits are shaped by broader social forces in ways we barely perceive, forming an unspoken but shared common ground. Here I’m building on the writing of Raymond Williams and what he called the structure of feeling, that unconsciously shared pattern of impulses, restraints, tones that simmer below the surface in particular times and places.

For example, over the last eighteen months, I have been undertaking a series of experiments in Berlin, Hong Kong, Colorado, Melbourne and New York that are trying to explore some ideas about how motion has become a key anxiety of our time. ‘Travelling Light’, which I last showed in Melbourne in late 2017, examined our paradoxical relationship with mobility. While those with money and visas celebrate the joy of motion and the possibility of travel, the knowledge that our current hypermobility is environmentally destructive travels with us. Our motion is also haunted by another shadow, the forced movement and constrained mobility of those whose cannot remain in their homes but who are unable to cross borders. Televised images of refugees in Europe were streaming into my Berlin studio when I embarked upon this series of works. Travelling Light explored the way that these new valences of mobility form a kind of structure that molds our thoughts and feelings, how this structure creates a contradictory set of impulses and hesitations that are widely shared.

CB: Your practice has drawing at the centre of your work. Yet we are not talking about a traditional approach such as a line on a flat surface. What is drawing?

HQ: I quite like something Robert Ryman once said about his practice, that any of his works that use lines are drawings. This is a position I adopted very early in my practice, but it really just defers the question to be ‘What is line?’ I interpret ‘line’ very liberally, to include two- and three-dimensional lines, sound lines, lines created by motion, architectural and environmental lines, and all the rest.

Having said that, I think what makes the context of drawing important for me is the artistic tradition of drawing with which I engage. I locate my practice in the field of expanded drawing, grounded in the work of modernists like Gego.

CB: Space appears just as essential to your works’ existence as the object or work of art themselves. How do you perceive space in relation to your work, such as the structure of the physical space or gallery and the volume of space or spaciousness existing within it?

HQ: That’s a great question – I’ve spoken already about line, but you cannot think about line without thinking of its negation, the surface ground for two-dimensional drawings, or space in the case of three-dimensional work. My approach to this is summed up in something Alain Badiou wrote about drawing:

“In one sense, the paper exists, as a material support, as a closed totality; and the marks, or the lines, do not exist by themselves: they have to compose something inside the paper. But in an other and more crucial sense, the paper as a background does not exist, because it is created as such, as an open surface, by the marks. It is that sort of movable reciprocity between existence and inexistence which constitutes the very essence of Drawing…” [1]

When I am working on three-dimensional drawings, I spend a lot of time thinking about how the drawing is creating the space around it. I don’t think of my artworks as passive objects sitting on the wall. They are active agents which produce the space around them. The precise parameters of this are guided by the goals of the work itself.

CB. Where do your drawings exist in time? This aspect of your practice is also something you stretch to extend its boundaries. For example, works you have created in Berlin as performance works take new forms as two dimensional, large-scale monochrome wall drawings, or even as ephemeral works such as your salt drawings. Can you speak to us about temporality, your sense of the moment, of past and future in relation to how you see your works?

HQ: There is sometimes a tendency to label some artworks as ‘durational’, in contrast to regular artworks which are presumably non-durational. It is the longevity of particular types of artworks, such as paintings on linen and stone sculptures, that led Hannah Arendt to mistakenly label durability as the distinguishing characteristic of the art object, but of course we have known since the 1960s that this is not the case. All art objects have a rhythm and a duration, whether long or short, fast or slow, and so all artworks are dealing with time, whether their creators realise it or not.

I try to bring a sensitivity to the temporality of art objects into my practice, rather than just assuming everything will last forever. In this way, temporality becomes a parameter of the artwork itself. I try to match the rhythm and duration of an artwork to its conceptual and aesthetic aims. While I still make many artworks that are long lasting, I try to make this a conscious choice, rather than an unquestioned and unseen default.

But there is more to temporality than this. Just in the same way that a drawing creates its surface or ground, so too do artworks produce the duration around them. And this does not always work in the way you would expect. For example, art works that only exist for a short period, or an instant, often attract a longer span of more focussed attention from audiences than static art objects that will last for hundreds of years. Art works of short duration seem to fashion a thicker – a denser or more compacted – quality of time around them. I am interested in experimenting further with this formal property of ephemeral art works.

CB: Metal and wire is a medium not usually associated with amorphous and fluid emotions, however you seem to be able to transmit a current and energy through your work, quite literally with your neon works. What made you take that leap to lighting your works? What is the emotional experience you want to elicit or transmit in the exchange?

HQ: Perhaps I am unusual in this, but I always find wire and metal to be very expressive media. The aluminium wire I now use is sensitive to touch in the same way that a photographic film is sensitive to light. Even less directly malleable materials like steel become flexible and responsive if you treat them with heat and weight. Whatever materials I use, I try to make sure that they impress the gestures of my hand like clay can impress your fingerprint. But in addition to embedding traces left by my hand, I also like to think about how the artworks feel under someone else’s touch, especially someone who couldn’t see the artwork. It’s almost like I’m holding hands with the person looking at and touching the artwork – and there are few ways of transmitting emotion more intimately than that.

There’s sometimes a tendency to see steel as an especially masculine material, particularly given the male-dominated history of blacksmithing. For example, many female sculptors in the past (but of course not all) have tended to favour softer and more domestic materials like latex, rubber, fibre or found objects, and leave traditional sculptural materials like metal and stone to men. I guess I want to push back against this cultural assumption – firstly because women can both work in ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ materials, but also because the materials themselves need not be gendered in this way. Just because steel tends to be used in harsh and angular ways, it doesn’t mean it has to be. Steel can be just as soft, liquid and responsive as latex if it is treated right.

Whatever materials I use, I try to make sure that they impress the gestures of my hand like clay can impress your fingerprint. But in addition to embedding traces left by my hand, I also like to think about how the artworks feel under someone else’s touch, especially someone who couldn’t see the artwork. It’s almost like I’m holding hands with the person looking at and touching the artwork – and there are few ways of transmitting emotion more intimately than that.

The decision to use lines of light has been quite recent, but my interest in light has been there since the beginning. Whenever you use three-dimensional materials like wire to create lines, you are also creating shadows. This has been a significant part of my practice for many years, and provides a visual bridge between my two- and three-dimensional works. So I have been thinking about light in various ways for quite some time now, and I guess it’s a natural progression from there to want to work with self-illuminating lines. But it was only after seeing very different but complementary exhibitions by Tokujin Yoshioka and Julio Le Parc that the idea of using lines of light directly really crystallised.

Travelling Light from Hannah Quinlivan on Vimeo.

CB: You bring performers in as part of your practice, such as singers and dancers, interacting with and sometimes even wearing your neon lit wire works. Do you collaborate with the dancers and singers or direct how they will move and sing? What constraints do you put around that as the artist? What freedoms do you allow them to express their own emotion, movement and flux in reponse to the space?

HQ: I’ve been working with contemporary dancers since 2012 – in fact, I was once a dancer myself, many years before I started making visual art. I think of motion as the unfolding of a drawing in time and space, and the human movement of a dancer is no different to this. I prefer human movement to the static mechanical movement of a machine for the same reason that I like to work in line with malleable, tactile materials like aluminium wire. They both express human gesture, it’s just that dance does so directly, while wire lines do so at one remove. When you touch a wire drawing, it quivers as if it has had life breathed into it. So I suppose I think of my wire drawings as dancers already, with their own heartbeat or pulse. It is only a small step from there to work with human dancers directly, to use the human body to extend and mobilise the line I can draw myself. The use of classically-trained vocalists is part of a more recent series of experiments that are concerned with materialising structures of feeling. There is certainly something linear or drawing-like about human singing: we speak about the lines of song, and it has the same structural qualities of length, intensity, rhythm and tone that we associate with drawings. In this way, I think about singing using the framework and categories derived from the tradition of drawing, rather than from opera or music. Singing becomes just another medium for drawing with, although it’s not one I’ve been able to technically master myself, hence the need for collaboration!

I think of motion as the unfolding of a drawing in time and space….

In answer to your question, my experience has been that successful collaboration requires trust and complete honesty. I need to be very clear about what I am trying to achieve in the artwork, and suggest parameters around the quality of the vocal line I am hoping to produce. But within these parameters, my collaborators have a great deal of autonomy, tethered to the structure I have created but free to experiment within those constraints. I have been incredibly lucky to work with people who are able to grasp what I am trying to achieve and translate that into their own area of expertise.

CB: What were some significant turning points for you in your art practice and development as an artist and in your career?

HQ: Probably the most crucial thing has been being supported by very committed commercial galleries since the start. They’ve been huge supports in all kinds of practical ways – but most of all, the financial support that a gallery can provide has allowed me to focus all of my energies on making, thinking and experimenting since 2014, instead of having to juggle multiple paid jobs separate to my practice. The luxury of time has been the most important thing of all, as all of my work is hugely time consuming – but the freedom of working as an artist has also provided me the capacity to travel and see and make art in places a long way from home. In particular, three residencies in Berlin have been crucial in testing out new ideas in a supportive and stimulating context. Ever since I began as an artist, there have been continuous cuts to government funding of the arts and a reduction in the number of visual artists practicing in my home country of around 15% over the last decade – I think that in this economic climate, non-government support is more important than ever.

CB: What has been the value of Mentoring for you? Can you tell us a bit about your experience and further what you then did to pass it on for other artists?

HQ: I’ll be forever grateful to Berlin-based artist Monika Grzymala for her on-going mentorship and guidance since 2013. She is an amazingly generous and insightful artist and teacher – she’s given me the opportunity to watch her work and learn from her own experiences, as well as guiding me in my practice at crucial times. Whenever I encounter obstacles in my art making or professional practice, I always ask myself what she would advise and I know right away what to do. She was also the first person I knew well who was working as a full-time artist and has been an amazing example of how to make that career life-sustaining. I owe a great deal to Monika professionally and personally.

My first trip to visit Monika in Berlin was funded by the Australia Council under their ‘JUMP’ mentorship scheme, which provided funds to support my travel and accommodation to Berlin, as well as a small honorarium to my mentor. I was among the last cohort of artists to be able to apply for this support before the scheme had its funding cut. Having seen how significant a difference this program had made for me, I was determined to set up a similar program. With a group of colleagues, I was able to set up a year-long mentorship programme to connect graduates of the ANU School of Art with senior artists in their local community. This program was a great success both for the mentees and in fostering inter-generational connections within the local art world. However, it’s a slightly bittersweet story, as we were ultimately unable to gain long term funding to continue this on either! I hope to revive the programme in a different form in years to come though… watch this space!

CB: What is something you do daily (or regularly) to sustain you as an artist?

HQ: My most important daily practice as an artist is to make. I work out my ideas through making and working, and it’s really the ability to do this regularly than helps me to break into new territory.

CB: Your exhibition “impulses, restraints, tones” has just opened in New York and is showing at Jankossen Contemporary in Chelsea. What can you tell us about the work and about the experience of bringing it together?

HQ: As we do this interview, I’m sitting in a small café in Williamsburg, New York, having almost finished a two-week salt drawing in Jankossen Contemporary in Chelsea. The show is really a culmination of the series of experiments I have undertaken over the last eighteen months, organised around William’s notion of ‘structure of feeling’.

It’s been a great experience showing with Jankossen Contemporary. I’ve been making here in Brooklyn for the last two months, finishing off the work for the show and seeing a lot of shows here in museums, art fairs and smaller venues. It’s been incredibly rewarding having my work exposed to a completely new audience.

Hannah Quinlivan’s solo show ‘impulses, restraints, tones’ is showing until April 20 at Jankossen Contemporary, New York.

I: @hannahquinlivan

Represented by:

Flinders Lane Gallery, Melbourne,

Jankossen Contemporary, New York and Venice

.M Contemporary, Sydney.

[1] Alain Badiou, 2011. ‘Drawing’, The Symptom, 12. http://lacan.com/symptom12/drawing.html